Trauma Informed Stabilisation Treatment for Structural Dissociation

The Structural Dissociation Model

Understanding the theory of structural dissociation by Vanderhart, Nijehuis and Steele and how Trauma informed stabilisation treatment (TIST) developed by Dr Janina Fisher works with complex trauma.

WANT TO LEARN MORE ABOUT COMPLEX TRAUMA? YOU CAN PURCHASE MY SHORT ONLINE COURSE ON UNDERSTANDING COMPLEX TRAUMA HERE.

Learn About Complex Trauma

UNDERSTANDING COMPLEX TRAUMA mini-course | $22 AUD

What is Dissociation?

Dissociate and its synonym disassociate can both mean to separate from association or union with another. When thinking about dissociation in therapy, we can think of dissociation as a severance of connection from ourselves. The term dissociation was used therapeutically by French philosopher and Psychologist Pierre Janet in the 1900’s, in reference to dissociation of the personality, rather than dissociative symptoms whereby people experience ‘altered states of consciousness but not fragmentation of the personality.

Today when therapists use the term dissociation, they often use it in a broad way to describe 'symptoms of dissociation rather than to describe dissociation of the personality. This can cause some confusion as dissociative symptoms may be part of what a person with fragmentation of the personality experiences but they are NOT dissociation of the personality.

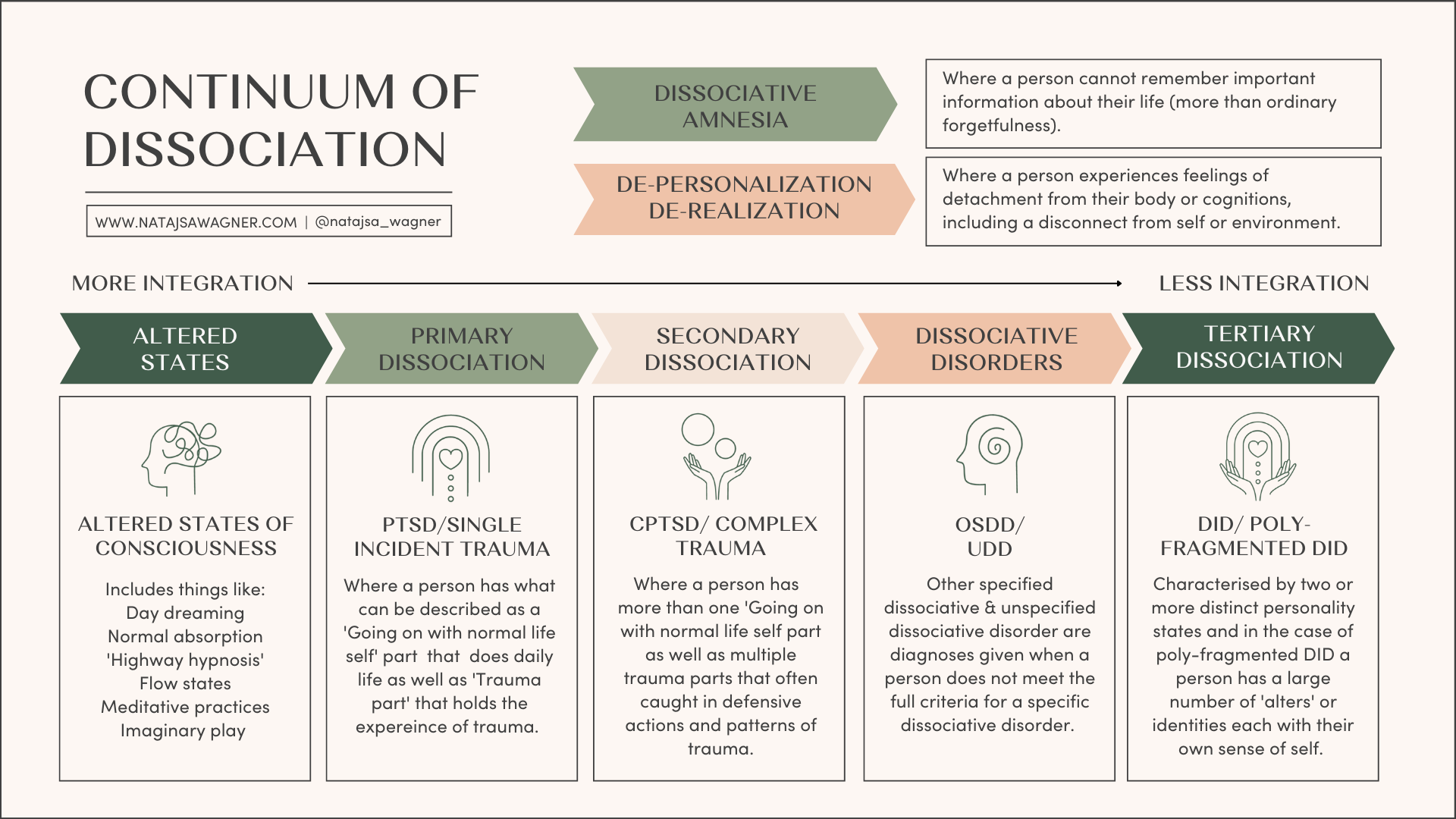

Dissociation symptoms range from more ‘every day’ altered states of consciousness like being absorbed in a task, daydreaming or accessing a flow state to more ‘pathological’ states where a person experiences more fragmentation of their personality and feels less like a ‘whole’ or individual self.

Dissociation can be broken down into different experiences on a continuum, including:

Altered states of consciousness, one example being when a person is out of their window of tolerance and in ‘hypo-arousal’. Some common feelings in this state are ‘feeling like I left the room’, ‘I am out of my body’ or not feeling present, unable to think, act or feel.

Fragmentation of a trauma memory, where a person does not remember a traumatic event or they may only have flash backs, implicit memories like body sensations and feelings.

Structural dissociation fragmentation of parts of the personality or self.

I have added an image that provides a brief outline to illustrate my version of a ‘continuum of dissociation’ that is hopefully a helpful guide to understanding the various descriptions of dissociation that people may be referring to when using the term dissociation.

This blog will be speaking to the theory of structural dissociation and fragmentation of the personality rather than just speaking about what I refer to as altered states of consciousness or symptoms of dissociation. There are also other theories around dissociation that may feel supportive for you to look into. As with all frameworks and theories, there is no perfect or right one, sometimes the language in many of the theories needs to be changed. Some clients and myself have found parts of this theory to be ableist, hence some of my changes and tweaks in language and description. The best way to learn about dissociation is to listen to people who have a lived experience of dissociation and to hold your frameworks lightly. I hope you find this information helpful.

Continuum of dissociation

How does dissociation happen?

Since the 80’s research around dissociation and dissociative identity disorder (DID) has seen a correlation in higher dissociation scores and/ or a dissociative diagnosis strongly linked to acute and chronic traumatic experiences. The data is clear in showing us that regardless of whether a person experiences trauma as a child, adolescent or adult, the greater the severity of the trauma and chronicity the higher the increase in dissociative symptoms and the more likely a person is to receive a diagnosis of a dissociative disorder. Some of the studies have included victims of childhood maltreatment and/or neglect, adult rape, combat, prisoner-of-war (POW) experiences, torture, trafficking, genocide, civilian dislocation during wartime, repeated painful medical procedures, accidents, and natural disasters.

These studies also show that earlier traumas that were cumulative and repetitive as well as early attachment trauma, particularly disorganized attachment strongly predicted elevated dissociation scores for people later on in life and/or development of a dissociative disorder.

In their book Treating trauma related dissociation Vanderhart, Steele and Boon explain that dissociation of the personality is maintained over time by:

a) chronic breaking points;

b) the inability to expand integrative capacity;

c) the necessity of relating to caretakers who are simultaneously needed and dangerous;

d) lack of social support, attachment repair and regulatory skills; and

e) conditioned phobic avoidance of a person’s inner experience

What is structural dissociation?

The theory of structural dissociation of the personality is a trauma model and comes from the work of Van der Hart, Nijenhuis and Steele’s (2006) The Theory of Structural Dissociation of the Personality. The model characterises people with complex trauma as having a division of their personality. This can be described as people having a range of different ‘parts’. A simple way to understand this division that can occur is through the natural division of the human brain, as we all have a left and right hemisphere.

Human brains are designed to split if things get too much or too overwhelming... the split between the two hemispheres enables the left-brain aspect of self to ‘keep on keeping on’... while the right brain mobilises the “corporeal and emotional self” (Cozolino, 2002), with its more physical survival resources (Fisher, 2017). This quote highlights how the left-hand side of the brain works to continue on with day to day life despite traumatic experiences and the right-hand side of the brain holds the experience of trauma and our emotions.

A person’s going on with normal life parts and trauma parts remain split off from one another or unintegrated, meaning that many trauma parts are stuck in patterns of traumatic experience and unhelpful behaviours as they hold the memories of trauma that have not been able to be integrated and resolved by the person.

Structural dissociation can be understood as:

1. Primary dissociation, often seen in a single incident trauma or with PTSD

2. Secondary dissociation, often seen in complex trauma or with C-PTSD

3. Tertiary dissociation, seen in extreme and chronic complex trauma

Below is a brief summary of the different types of structural dissociation.

Note: In this blog, I have used the term ‘Going on with normal life self’ rather than the Apparently normal part or ANP to describe the left-hand side of our brain and ‘Trauma Part/s’ rather than Emotional part or EP to describe the right-hand side of our brain. (This comes from Dr Janina Fishers work and it is a personal preference around language that varies from the terms used in the original theory of structural dissociation)

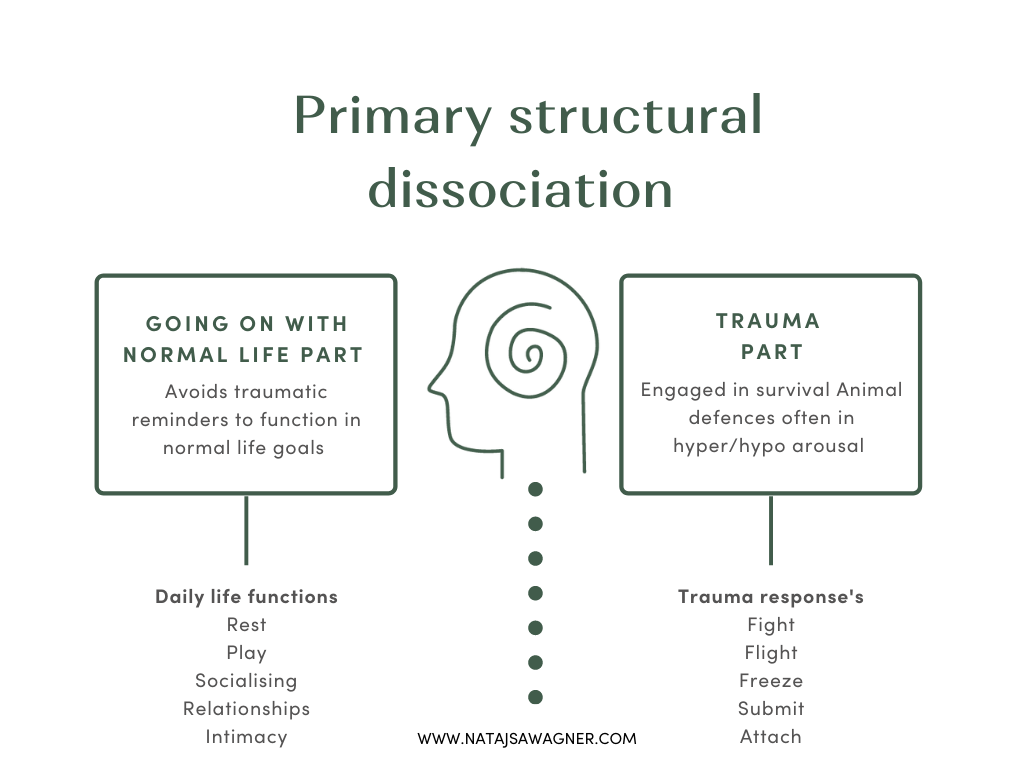

Primary structural dissociation

Primary structural dissociation is generally characterised in trauma-related experiences such as post traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) and involves a single “going on with normal life part’ and a single ‘trauma part.

In primary structural dissociation, the going on with normal life part is tasked with the dual tasks of living daily life despite traumatisation and avoiding traumatic memories. The traumatized part is the part that is fixed in trauma memories. It may hold different memories and emotions as well as internalised messages and core beliefs.

The trauma part is kept from integrating with the going on with normal life self because it holds the traumatic experiences and memories that could overwhelm the self and prevent the person from being able to function in their day to day life. This means that a person’s fight, flight, freeze, and submission responses to trauma and the memories and internalised messages associated with them are dissociated, or not integrated, with the going on with normal life part.

For those with PTSD, this allows the going on with normal life part to remain numb and avoidant towards the traumatic memories and experiences except when something triggers the trauma part.

When this happens the trauma part is activated alongside the going on with normal life part and the person experiences the trauma intruding into their life, commonly through, dissociative flashbacks, hyper vigilance, feelings of panic, overwhelm, irritability and recklessness, emotional outbursts, negative thoughts about the world, others and themselves, nightmares and other somatic symptoms.

This is experienced a bit like a hijacking where it feels like the trauma is happening right now in the present rather than back then in the past.

A person’s early experiences and development are one of the factors that can play a role in structural dissociation. When a person has had a relatively safe, secure and consistent childhood they are able to fully develop their personality, they have a sense of self and identity that feels integrated, cohesive and whole ( as is often the case in primary structural dissociation) however a combination of genetics and trauma or extreme stress can also cause a person to dissociate later in life, leading to dissociative challenges such as depersonalization/derealization disorder or dissociative amnesia or to a trauma- and stress-related disorder and most notably (PTSD). Early life trauma can also lead to the same disorders when the individual is more resilient, when the trauma is not a betrayal-trauma, when the trauma is not repeated, or simply when the individual is not as genetically predisposed to dissociative responses.

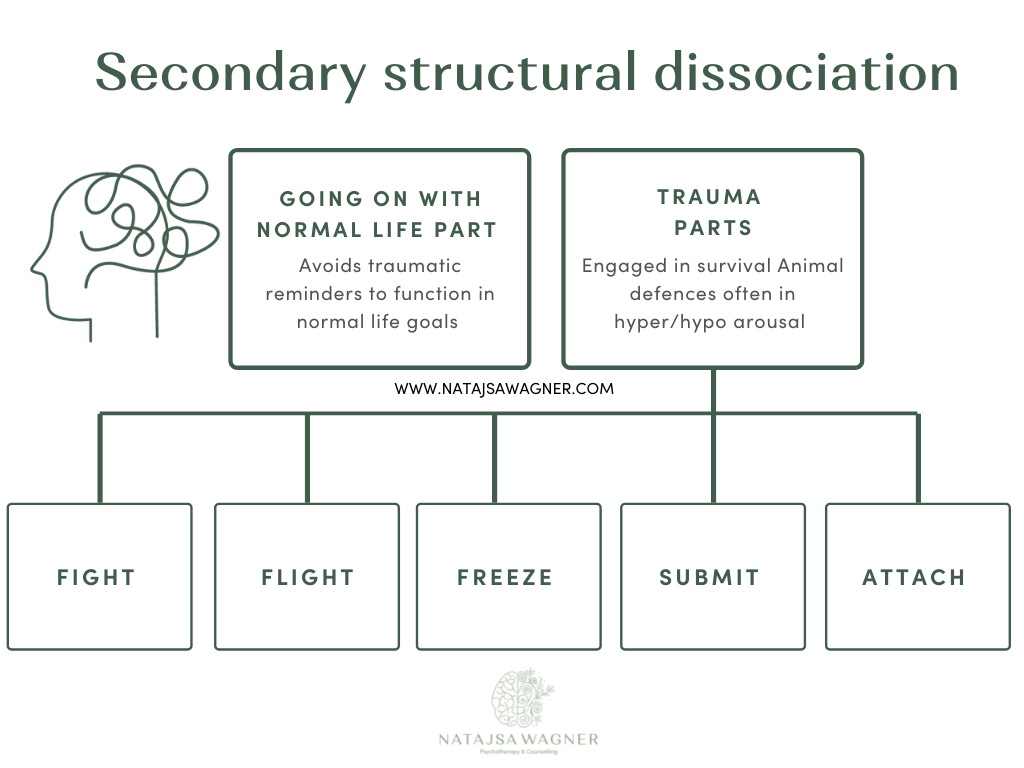

Secondary structural dissociation

Secondary structural dissociation is generally characterised in multiple trauma related experiences such as complex post traumatic stress disorder (C-PTSD) and involves a single going on with normal life part and multiple trauma parts within an individual.

When a person has experienced trauma at a younger age or before certain parts of the brain have fully developed the may have a less integrated personality or sense of self. Repeated trauma that occurs over a period of time also requires a person to find a way to contain more and more traumatic material and memories. Trauma that is perpetrated by someone who has a relationship with the child and who is supposed to protect a child creates a strong motivation for the trauma that the child experiences to remain split off. This is so the person is able to remain unaware of the trauma they have experienced, and in doing so the person can go on with their daily life.

Additionally, when a child has experienced disorganised attachment (see blog on attachment) and their two opposing biological drives of attach and defend are stimulated at the same time, the child learns to adapt and react in conflicting ways to a caretaker without allowing any of their other learned responses to come through.

As in primary structural dissociation, the going on with normal life part in secondary structural dissociation is responsible for managing day to day life tasks while multiple trauma parts hold the traumatic materials that the going on with normal life part could not integrate. Instead of just one trauma part as seen in primary dissociation, the trauma parts’ of the self becomes more compartmentalised in secondary dissociation. Separate subparts evolve reflecting the different survival strategies and complexity needed in a world that is dangerous and un-safe. The trauma parts may also be more highly developed than are those in primary structural dissociation.

Trauma parts are sometimes categorised and referred to as animal defence survival strategies against trauma, namely:

Fight: A fight part is often hypervigilant and on guard. They may also be angry, judgemental and blaming towards others. Fight parts hold self harm behaviours and suicidality and has access to aggression.

Flight: A flight part is looking to escape. This can be seen in a number of ways including being distant, strong ambivalence, addictive behaviours or eating disorders that support the person to escape or numb painful thoughts, feelings, emotions and sensations.

Freeze: A freeze part is fearful. This can be seen in the part being frozen, terrified, wary, phobic of being seen. A freeze part will often isolate and may be agoraphobic, have panic attacks and experience anxiety.

Submit: A submit part holds shame. This can be seen in the part having strong feelings of hopelessness and depression, being ashamed and filled with self-hatred. This part is the opposite of the fight part or aggression. It is passive, looks to be the “good child’ and is often people pleasing and self-sacrificing.

Attach: An attach part feels lonely and abandoned. This part can experience a deep need for connection, that feels like the desperation of a small child. The attach part craves rescue and connection and is often sweet and innocent, with a desire to depend on others.

When each of these parts are active, they are in ‘trauma time’ and are engaging survival strategies. The parts are trying to to fight back, they may be freezing or fleeing or going into a shut down/submit response or an attach cry for help.

Its important to understand that all of these parts hold survival strategies that once reduced the level of harm a person experienced and helped an individual to survive. The challenges is that these strategies have now become split off automatic responses that are activated when a person is triggered by trauma related stimuli (something a person takes in through their senses eg an image, smell, sound or touch) related to a traumatic event.

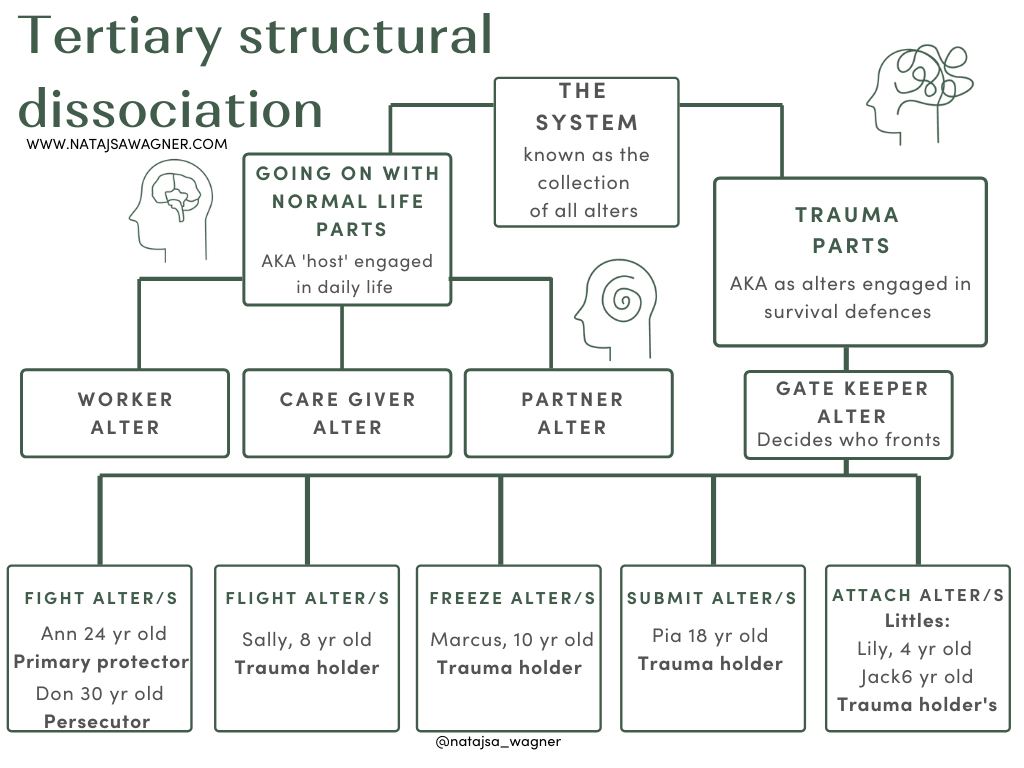

Tertiary structural dissociation

Tertiary structural dissociation is generally characterised by multiple, serve and long lasting, complex trauma experiences as in the case of DID. Tertiary dissociation involves multiple going on with normal life parts as well as multiple trauma parts within an individual.

In tertiary structural dissociation the going on with normal life parts may each handle different aspects of a person’s day to day life. For example, a person may have a going on with normal life part that has the role of being a caregiver as well as another going on with normal life part that has the role of being a working professional and another going on with normal life part that has the role of being a partner.

A going on with normal life part may be referred to as a ‘host personality’ or host as they are the identity that most frequently manages the body and day to day life. Going on with normal life parts do not hold trauma memories.

As in secondary structural dissociation trauma parts of the personality hold traumatic memory and are often stuck in the experiences and survival defences associated with trauma. Parts that hold traumatic memories help, because the rest of the system does not have to know about the memories and the going on with normal life parts can focus on day to day life and continue to function. The challenge, is that the parts who hold the trauma memories are often living in ‘trauma time’ consumed by their experiences, seeing and feeling everything through the lens of their traumatic experiences. this can result in the past feeling like it happened only yesterday or that it is still happening now.

Some parts may also hold emotion, particularly if there is a certain emotion that feels difficult to cope with. Having a part hold the difficult emotion may make life feel more manageable, because if one part can contain all or most of that emotion, then the other parts do not need to feel it. The difficulty with one part holding these difficult emotions is that this part will often experience the emotions with much intensity and overwhelm.

In DID both the going on with normal life parts and trauma parts may be referred to as parts, aspects, alters, head mates, friends. Many people have different preferences around language, so it’s important to always ask people how they relate or what words works best for them.

An alter can be described as a dissociated self state that may be associated with either dissociative identity disorder (DID) or other specified dissociative disorder subtype 1 (OSDD-1). Alters may or may not be aware of each other or that they are part of a whole. They experience themselves as completely unique individuals and may view the other alters as either completely separate individuals or experience them as ‘me but not me’. Alters have different thoughts, perceptions, and memories relating to themselves and to the world around them.

Alters may also speak to having a certain age, gender identity, sexuality, appearance, source, or even species. Some alters may see what they expect to see when they see their reflection in a mirror, whilst and others experience disbelief and distress when they see that the body that they are in does not match their idea of how they believe they should look. Alters will often reject the idea that they are only an aspect or part of a complete person.

Alters are also referred to as parts, alternate personalities, personalities, fragments, "head mates," internal family members like sisters, brothers, cousins etc), or self states. You can read more about the different type of alters that may be present for a person here.

The word system is also used to describe the collection of alters that exist.

Dissociative Multiplicity and Psychoanalysis from Dissociation and the Dissociative Disorders: DSM-V and Beyond shares this important information:

"The alters may be few or many, of various ages, including older than the body, same- or cross-gendered, hetero- or homosexual, alive or dead, with either or both co-consciousness and co-presence to varying degrees, which may not be commutative (i.e., may be one-way), communicating not at all, or through hallucinations, or through direct thought transfer, manifesting different physiological signs in the body when out, clustered in various arrays of dyads, subgrouping, layers, purposes, and so on. Subhuman, animal, or imaginary alters are not uncommon, with likely links to children’s fantasy. When out, a given host or alter may appear globally to be mentally and behaviorally whole and normal or an exaggerated caricature or a single-function agent, and so on, but not necessarily congruent with the age and gender of the body" (Dell & O'Neil, 2009).

The trauma parts of tertiary structural dissociation are most like those found in OSDD-1. However, these trauma parts are likely to be more complex and well developed than those typically found in secondary structural dissociation. Often certain emotions and triggers of traumatic memories can cause other parts to become more present, influence the person or even take over for a while.

When an alter changes from one to another, this is known as a ‘switch’.

Switching can involve one alter taking control of the body, being given control by another alter. Generally in DID, most if not all alters are able to take on control of the body in which they reside.

More than one alter can be present at the same time and this this is called being co-conscious or co con for short.

When this occurs two or more alters are aware of the other's presence, and have an on-going memory of a situation or particular period of time. Whilst one alter may have more executive control of the person's body, another alter will observe, listen and think about what is occurring. Co-consciousness is an important part of improving day to day functioning and co-operation between alters as well as helping reduce amnesia.

For some people when one alter switches with another alter. they may lose time or have amnesia about what has occurred. Amnesia is one of the hallmark features of DID and one of the most frequently reported symptoms. For others a person with continual co-consciousness will not ‘lose time’ or experience amnesia in the present, however they may meet the diagnostic criteria for DID because they still have some amnesia for past events. If there is no amnesia for past or present events, then a person with alters is likely to fit the criteria for OSDD.

Switches can happen through what is known as passive influence, where there is an intrusion from another alter that isn’t prominent This is usually seen in an experience of thoughts, emotion and behaviours that feel alien. Memories that are received through passive influence may not remain once the influence is over, leaving the fronting alter unable to recall what the memory contained, alternatively passive influence may also lead to certain memories, emotions, sensations, or views becoming inaccessible to the fronting alter until the influence ends.

Below are some examples of common alters, this is by no means an exhaustive list as there are many other DID alters that have other functions and every system is unique but the following may be helpful in describing some of the common functions of alters. Please know that language is also important, again the best way to understand a system is to speak to them and ask their preference around language.

Examples of alters and their functions

Core: The core is may be known as the original or the original child, this is considered by some to be the part first born to the body. Some see the core as the owner of the system, the part that has the most power and influence over other parts, and the most important part which the other parts were created to protect. DID allows for many variations, and the absence, presence, or strength of one or more core or original going on with normal life parts is one such variable. A good explanation of the term core and how it relates to the theory of structural dissociation can be found here.

Protectors roles are as they sound, they are designed to protect the system, the body and other alters. A system may have have emotional protectors that take on emotional abuse and comfort other alters, physical protectors that enact aggressive behaviours or who step in to protect against physical abuse and sexual protectors that may engage in sexual affairs, regardless of consent. They are often looking to feel in control and they may be more sexual in nature, as a result of past trauma experiences, which can lead to further victimisation and unsafe situations.

Gatekeepers function to controls the “switching”, or whoever gets access to the “front”. A lot of systems call this process “fronting”. You can think of the gate keeper as the supervisor of the whole system.

Persecutors may seek to harm the system, body, alters, and/or destroy personal relationships and the body. The term misguided alters is often helpful because, all parts are trying to protect the system, in the way that they have learned, for these parts they are often misguided in their thinking and attempts to do so. They are often focused on the goal of controlling and ruling the system through abuse, they may be reenacting trauma, reasoning that more trauma isn’t harmful and will just balance things out. They may hold a belief that by hurting the system they will be able to protect it. They may also be fearful of good of pleasurable things like good new, experiences, and feelings. They may prefer to a get rid of them as a way to avoid feeling hurt or disappointed. Some protectors are introjects of abusers (see below) and may not understand that they themselves are not abusers.

Introjects may be alters based off other people. An example could be a supportive family member, teacher or friend who had a positive influence. They may also be a historical figure a child found strong, kind or courageous. They may also be abusers. In the case of abusive introjects, they may often re-enact past trauma to reinforce the ‘lessons’ from abusers. they may also not see themselves as the person they represent, they may also experience a level of self-disgust around ‘where they came from’

Fragments are alters who did not fully develop or don’t have their own unique attributes. They may exist to complete certain tasks, or maintain single memories and/or emotions. Individually, they may not encompass an entire person and need other alters to complete them.

Caretakers care for specific members of the system, like littles, pets, teens, animals and system groups. Their main role is to ensure the body is taken care of. They may act like a parental figure to other alters, and those they may be referred to as mother, grandfather or father by other alters in their care.

Trauma holders are also called memory holders because they hold the trauma. Each alter will also have other memories apart from atraumatic memories, however some may hold more trauma than other and also have fewer pleasant memories.

Children/little alters include young children, middle aged children and teenagers. Ages of each vary from system to system. Certain things can trigger them like names, objects and smells, which can mean that a child alter fronts and may get into an inappropriate situation that can be dangerous or unsafe.

What is Trauma Informed Stabilisation Treatment (TIST)?

Trauma Informed Stabilisation Treatment (TIST) is a model for working with people who have experienced complex trauma and who experience structural dissociation. Childhood trauma including adverse childhood experiences like neglect, and abandonment leave people with overwhelmingly painful memories, emotions and a compromised nervous system that impacts on their capacity to tolerate the challenges of day to day life and the trauma-related activation that happens when a person in triggered.

Many people who have experienced complex trauma are unaware that the intense and overwhelming thoughts, feelings, sensations and reactions they experience are driven by implicit trauma memories that the body remembers and not necessarily the experiences of what is happening in the present.

When faced with these painful and overwhelming thoughts, feelings and sensations a trauma survivor may resort to finding ‘survival adaptations’ or coping strategies (ways to regulate the distressing thoughts, feelings and sensations, that were once helpful, but have now become chronic, unhelpful or dangerous) to manage the overwhelm they feel, and to get some fast, but short-term relief.

Survival adaptations can take the form addictive behaviours like disordered eating, and substance abuse to numb emotions or to alter states of consciousness. Other coping strategies can include self-harm to dissociate and feel relief temporarily or suicidal ideation is often a way of trying to feeling in control.

TIST or Trauma-Informed Stabilisation Treatment is a model for working with complex trauma developed by renowned trauma expert Dr Janina Fisher. TIST is based on theoretical principles drawn from the neuroscience research on trauma and structural dissociation theory. It is an approach that integrates mindfulness-based cognitive therapy, Sensorimotor Psychotherapy, ego state techniques, and Internal Family Systems.

Instead of assuming that ‘what you feel is who you are,’ clients are asked to be curious about their parts. They are asked to mindfully notice each part of themselves, so they can better understand what each part is trying to communicate around their fears and needs. With a focus on understanding the actions and reactions of parts as the understandable and instinctive responses to trauma, we can start to diminish the shame, blame and judgement trauma survivors often hold and begin to start the process of healing trauma.

TIST has been used successfully to address the challenges of treating individuals with diagnoses of complex PTSD, borderline personality, bipolar disorder, addictive and eating disorders, and dissociative disorders. The TIST model empowers trauma survivors and focuses on treating the effects of traumatic events and the legacy carried forward by parts holding the trauma, rather than focusing on treating the events themselves. TIST is about resolving the impacts of trauma not reliving the trauma.In TIST, the focus is on helping people feel more connected, accepting, and self-compassionate. TIST also follows the gold standard of trauma treatment by working with the three phase approach.

Natajsa is a Brisbane based Somatic Psychotherapist trained in TIST, Sensorimotor Psychotherapy and somatic experiencing. She also works with a range of additional somatic and cognitive approaches to support people who have experienced complex trauma. Natajsa is currently not accepting new clients, and is only able to take on 1-2 new clients per year, but you can join her waitlist to be notified if any spaces become available in the future. If you are looking for support with complex trauma you can contact the Blue knot foundation ( The national centre for excellence in complex trauma) on 1300 657 380 where you can receive telephone support or receive a recommendation to a trauma informed therapist.

Additional Resources to learn about dissociation:

The Film, Petals of a Rose: https://www.dylancrumpler.com/watch-petals-of-a-rose

An Infinite Mind: Created by a lived experience clinican: https://www.aninfinitemind.org

The Plural Association: The first and only not for profit that supports those who identify as plural: https://thepluralassociation.org

Learn About Complex Trauma

UNDERSTANDING COMPLEX TRAUMA mini-course | $19 AUD