Somatic Touch in Developmental Trauma

Therapeutic Touch & Healing Developmental Trauma

How Somatic Resilience and Regulation (SRR) therapy can support recovery from developmental trauma through understanding co-regulation and therapeutic touch.

Developmental trauma interrupts our ability to self-regulate and has profound impact on attachment, the relationship we have with ourselves, others and our physiology. This blog speaks about the therapeutic intervention called Somatic Resilience and Regulation (SRR) which was created by Kathy L. Kain and Stephen J. Terrell. SRR focuses on understanding the effects of Developmental Trauma where our experiences of attachment have in some way been disrupted. It discusses the concepts of allostatic load, allostasis and allostatic overload as well as the importance of coregulation and how we can support the healing of developmental trauma by helping people experience more regulation.

What is Developmental Trauma?

Developmental trauma refers to chronic and prolonged exposure to stressful or traumatic events during a child's early years, particularly when they are developing fundamental emotional and psychological foundations. This type of trauma can disrupt a child's sense of safety and security, impacting their ability to form healthy attachments and relationships later in life.

Developmental trauma significantly impacts the brain's development, particularly areas responsible for emotional regulation, stress response, and attachment (Schore, 2001). The lack of consistent and responsive caregiving can lead to insecure attachment styles, such as anxious or avoidant attachment (Bowlby, 1988). These attachment disruptions in our early relationships are significant as they form the blueprint for future interactions as adults and shape our emotional health and well-being.

When children feel overwhelmed, helpless or lack the support and regulated, attuned and present other (aka no opportunity to receive co-regulation) they are not able to regulate their own nervous system response by themselves. They may go into a state of flight or fight but more often the only available option for a child is to go into freeze, or a state of shutdown and collapse because children under the age of five are not able to regulate on their own.

The attachment research shows us that “good enough” parenting in childhood assists with the reduction of stress. This is done through co-regulation. If children are not able to get co-regulation (due to for example, parents are not physically/emotionally available, violence or abuse, mental illness/substance use, intergenerational trauma, illness, hospitalisation or other adverse childhood experiences), they may not develop the ability to self-regulate. Exposure to chronic stress with no access to a resolution moves a child into ‘freeze’ as their default physiology resulting in underlying dysregulation of the nervous system.

All of this can result in a child’s physiology not being able to do its job. The adrenal glands, which are important in helping stress hormones physically wash out of our system, become sluggish leaving those that remain in the body to become toxic. This can lead to a range of physical symptoms and health Challenges as Dr. Gabor Mate talks about this inhis book -When the Body Says No (2003).

One common sign of early trauma is a person’s nervous system operating in states of either high activation or complete shutdown. This is because many people who grew up in threatening environments and experienced early developmental trauma, do not have an experience of what it is in their body of ‘non-stress physiology’. The ongoing exposure to chronic stress and trauma without resolution places a demand on our physiology and the resources of our body.

Instead of being in homeostasis, where our body is in a state of natural equilibrium, using a small or appropriate amount of physiological energy to respond in the moment, people who have experienced developmental trauma have demands placed on the systems of the body. That demand in the body that says. Hey, we need to balance everything that’s going on here and this is where we see allostatic load.

What is Allostatic Load?

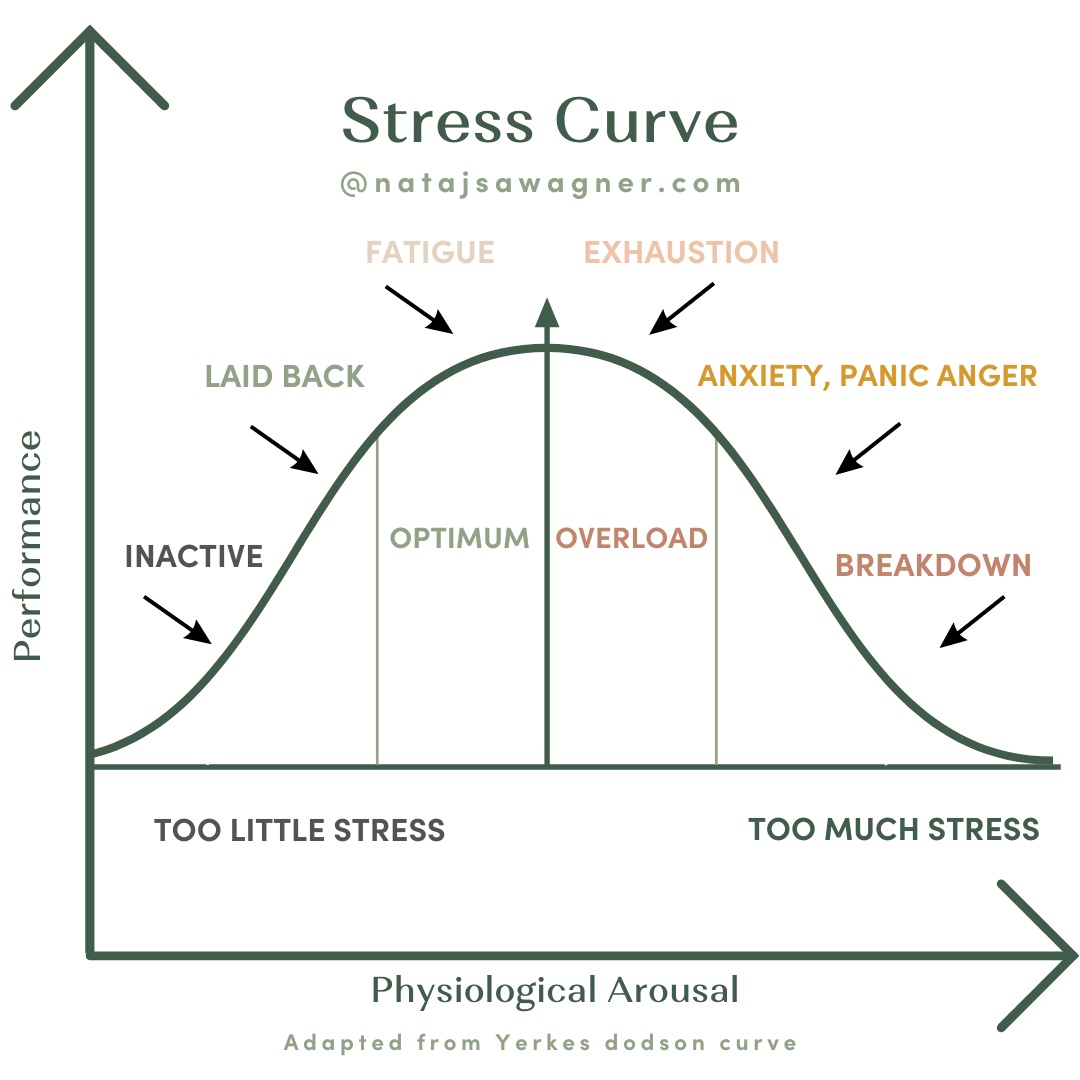

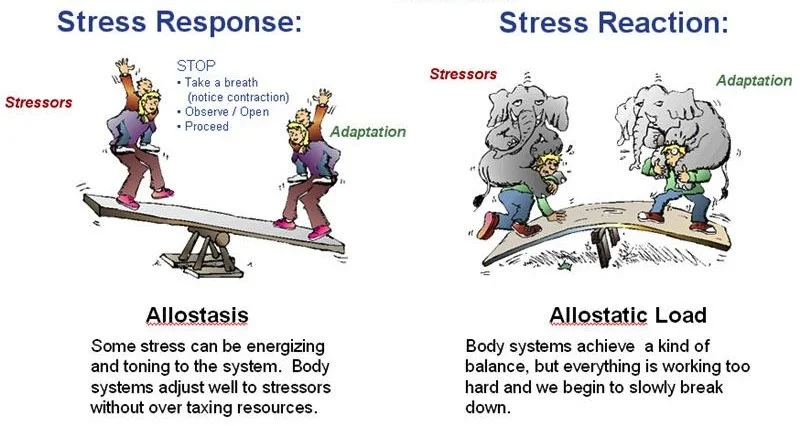

A simple image to show stress and allostatic load

Allostatic load is like the cost that we have to pay out of whatever resources we currently have. It refers to the cumulative wear and tear on the body's systems due to exposure to chronic stress and the constant activation of our stress response. It represents the physiological consequences of repeated or chronic exposure to stressors and the body's attempt to adapt to these challenges through allostasis. Over time, this continuous effort to maintain stability can lead to various health challenges that include metabolic, cardiovascular, and immune system changes. You can read about how your Adverse childhood experience (ACE) score correlates to higher levels of allostatic load HERE

Allostasis and Developmental Trauma

Allostasis is the process by which the body achieves stability through physiological or behavioural change. Unlike homeostasis, which refers to maintaining a constant internal enviroment, allostasis involves our adaptation to stressors and challenges by varying our internal environment so that we can maintain physiological functioning in the face of changing environmental conditions.

An example could be that in a stressful environment a person could maintain an elevated level of blood pressure relative to the level maintained in a less stressful environment. The process of allostasis is crucial for survival, but when it is constantly engaged, it leads to allostatic overload, as seen in the case of people who have experienced complex trauma and early developmental trauma.

The process of allostasis can look like:

Activation of Stress Response Systems including:

HPA Axis: The hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal (HPA) axis is activated in response to stress, leading to the release of cortisol and other stress hormones. In people with early developmental trauma, this system can become hyperactive, resulting in chronic cortisol release.

Autonomic Nervous System: The sympathetic nervous system is frequently activated, leading to the release of adrenaline and norepinephrine, which prepare the body for "fight or flight" responses.

Physiological Adaptations including:

Cardiovascular System: Increased heart rate and blood pressure prepare the body to respond to immediate threats.

Metabolic Changes: Mobilization of energy resources (glucose and fatty acids) to provide immediate fuel for the body.

Immune System: Acute stress can temporarily enhance immune function, but chronic stress can suppress immune responses, making the individual more vulnerable to illnesses.

Behavioral Adaptations:

Hypervigilance: Constant scanning of the environment for potential threats, common in individuals with a history of trauma.

Avoidance Behaviors: Efforts to avoid triggers or reminders of the trauma, which can interfere with daily functioning.

The Impact of Early Developmental Trauma:

Brain Development: Chronic activation of the stress response during critical periods of brain development can lead to structural and functional changes in brain regions such as the amygdala, hippocampus, and prefrontal cortex.

Amygdala: Increased sensitivity to perceived threats.

Hippocampus: Impaired memory formation and regulation of stress responses.

Prefrontal Cortex: Reduced ability to regulate emotions and behaviors.

Because allostasis involves ‘predictive regulation’ or stabilisation, in response to our environment and the stimuli we are picking up ( including through our internal sensations) our brain starts to anticipate our needs and tries to prepare so that we can meet those needs before and as they arise.

Allostasis helps us to do this by anticipating what we are going to need, and planning on how to satisfy them ahead of time. This takes a lot of energy from our brain to do this and if it is trying to do this all the time, yet failing to resolve the uncertainty of the situation or the chronic stress and trauma cannot be resolved, we start to see allostatic overload. In an ideal world, our nervous system looks more like an ebb and flow, it responds to the demands on our system with relative ease and we have moments of more sympathetic tone and moments of more parasympathetic tone as is the case with daily life activities like sleep, movement, exercise, work etc.

However with exposure to chronic stress and trauma, we have this high tone of sympathetic response in the nervous system ( you can think of it like the gas pedal of the car constantly revving, which can be experienced as being in fight or flight energy) or high tone parasympathetic (the body and nervous system is in a state of collapse or shutdown - think of this as the brake being on). There can also be a combination of this which looks like having one foot on the gas pedal and the other on the break, resulting in an experience of what could be called more ‘ functional freeze’ which means I am operating day to day, whilst my body carries a high allostatic load.

Our life is being led trying to manage our nervous system response with different types of coping strategies - external to us. This is because we are not able to get the co-regulation from our attachment figures, due to the chronic stress and threat or because our caregivers are not available or represent that threat. We learn to find ways outside of ourselves to try and cope.

In this way, you can think of people who are always outside what has been called a window of tolerance’ it may appear as though they can regulate themselves or that they have some ability to work with the dysregulation they experience, however they more in what we would call a ‘Faux window of tolerance’ and in this type of allostatic overload the system is failing, the person is finding it more and more difficult to even stay within the faux window of tolerance using external things like alcohol, other substances, sex, risky behaviours etc.

So similar to a person who is running a marathon, who keeps running marathon after marathon without a break, the body is not getting a chance to repair and recover from the physiological stress it experiences. If each day we go out and run a marathon without having the ability to rest and recover from the previous allostatic load we experienced we start to see a breakdown of the body’s physical symptoms as the body is working hard through the process known as allostasis to try and get us back into homeostasis. what’s important to remember about this process is that homeostasis works to try and be as efficient as possible, using the least amount of our energy possible to do the job at hand. The body will pull from our energy reserves or shut down systems that it deems as not necessary to try and maintain homeostasis.

Remember that whilst we are in allostatic overload, that feeling of running a marathon day after day due to the chronic and ongoing exposure to threats and stress it’s like we are doing a double duty shift, not only are we trying to repair from the previous allostatic overload were trying to run and function day to day as well.

So what happens when someone has early developmental trauma and the coping strategies they have used to try and keep them within some kind of window of tolerance albeit a faux window are no longer keeping them in range and they don’t get any recovery time? This is we see systems breaking down and people living in a state of allostatic overload.

Allostatic Overload

Allostatic overload refers to the cumulative burden and long-standing effects of a continually activated stress response in the face of chronic stress and life events that exceed a person’s ability to cope and adapt. This leads to physiological and psychological dysfunction and nervous system dysregulation.

In the context of people with early developmental trauma, allostatic overload becomes particularly relevant due to prolonged and intense exposure to stress during critical periods of brain and emotional development. When the adaptive systems are overused and fail to return to their baseline states, it can lead to chronic health problems such as cardiovascular disease, diabetes, anxiety, depression, C-PTSD and other major health challenges.

Key features of allostatic overload are:

Chronic Activation of the Stress Response: Individuals with early developmental trauma often live in a chronic state of stress, resulting in the constant activation of their stress response systems (e.g., the hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal axis and the autonomic nervous system). This persistent activation can lead to allostatic overload.

Physiological Impact: The chronic stress experienced by these individuals can lead to various health problems, including cardiovascular disease, metabolic syndrome, immune dysregulation, and neuroendocrine disturbances. The body's constant effort to maintain stability (allostasis) under chronic stress can wear down the biological systems.

Psychological Consequences: Allostatic overload can contribute to mental health issues such as anxiety, depression, and post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD). The brain areas involved in stress regulation, such as the amygdala, hippocampus, and prefrontal cortex, may be adversely affected, impacting emotional regulation, memory, and executive functioning.

Many people who have expereinced Developmental trauma live in a constant state of allostatic overload.

If we are living in a constant state of allostatic overload, our window of tolerance is going to decrease because there is no opportunity to recover and repair. There is no rest time. We can think of this as the energy demands exceeding our supply. Our systems begin moving us into survival mode as we try to decrease allostatic load and regain a more positive energy balance. We could think about an example of birds in the wild who have faced a hard winter and are about to go into a breeding season.

Imagine that a flock of birds has had a particularly tough winter due to bad weather. The birds work to maintain homeostasis but due to the allostatic load ( burden of stress, bad weather resulting in a reduction of food) this negative energy balance results in the birds experiencing weight loss, a suppression in energy, leading to a lack of reproduction as the bird is trying to maintain homeostasis, using the least amount of energy possible to survive and do what it needs to do with minimal effort.

We can see the same things that start to happen for us as humans in terms of our body’s systems shutting down in the face of allostatic load trying to survive, and when the body is not able to recover on its own, we go in search of things externally to try and get support for our system to get back into some kind of regulation.

We go external because due to the chronic and ongoing stress we have experienced our ability to engage the parasympathetic nervous system is now not functioning on its own as it should be. We need all of these other coping strategies to try and feel a bit better and stay alive because the biological and physiological resources that are internal to us are not functioning.

For people who have experienced developmental trauma, the goal of regulation through teaching self-regulation skills is not enough. This is because we are working with people who have little to no experience of being able to do self-regulation. Their nervous system has not developed in the same way as someone who may have had more supportive, nurturing and attuned experiences of co-regulation. There has been no ability to internalise and take on these experiences that support the body to move into regulation.

The goal is to help people with early developmental trauma to experience more moments of regulation through experiences of co-regulation. Supporting people to get to a new ‘set point’, means that the systems of the body do not have to work so hard internally. Because remember, a person's system is already in allostatic overload and we don’t want to be placing more and more demand on a body and system that is already in overload. This means we also have to work gently, slowly and in a way that the person’s body isn’t being thrown into another state of demand and overwhelm.

Again, regulation can't happen through teaching self-regulation skills alone, because many people who have had experiences of developmental trauma do not have the experience of regulation to go back to and draw upon. Often there are limited or even no experiences of a felt sense of safety in a person’s history. Coming into therapy for many people is the first time the potentially have access to an experience of safety.

We can see the same things that start to happen for us as humans in terms of our body’s systems shutting down in the face of allostatic load trying to survive, and when the body is not able to recover on its own, we go in search of things externally to try and get support for our system to get back into some kind of regulation.

We go external because due to the chronic and ongoing stress we have experienced our ability to engage the parasympathetic nervous system is now not functioning on its own as it should be. We need all of these other coping strategies to try and feel a bit better and stay alive because the biological and physiological resources that are internal to us are not functioning.

This also means that until we can accumulate enough new experiences of safety to update what is in the ‘filing cabinets’ or the experiences and memories of threat that we may have grown up with to outweigh or offset those experiences of threat we are going to continue to interpret things as dangerous.

This could be a facial expression, a sensation we experience, or a word. We all have our own historical reference system and our amygdala ( the part of our brain that responds to threats) has a huge filing cabinet with all the accumulated threatening experiences we may have had. We know you can't talk someone out of fear, instead, we have to work to build up a different reference system over time, slowly working towards more accurate interoception and more moments of safety.

What is Therapeutic Touch & How Does it Help With Developmental Trauma?

Somatic Resilience and Regulation (SRR) Therapy is a one type of therapy that is designed to act as an intervention to the reaction of stress in the system. It was created by Kathy L. Kain and Stephen J. Terrell, senior Somatic Experiencing Practitioners and Teachers of Peter Levine’s work. They developed Somatic Resilience and Regulation in response to the need for more specific and titrated approaches for people who have experienced early developmental trauma. Their work blends Attachment theory, Poly-vagal Theory, Neuroscience, body work, and somatic’s to provide a new way to understand and work with safety and regulation. Kathy and Stephen also co-authored the book Nurturing Resilience: Helping Clients Move Forward from Developmental Trauma.

SRR is a gentle and non invasive therapy that makes use of therapeutic touch as well as intentional touch ( non physical specific intentional attention and attunement) that works directly with the threat response systems of the body including the Hypo pituitary adrenal (HPA) axis which includes the Hypothalamus (which activates responses of fight, flight or freeze.) The Amygdala which decodes and sorts emotions while at the same time, determining the possible threat and storing fear memories. The Pituitary Gland, which controls the function of most other endocrine glands by producing and releasing a number of different hormones. Each hormone affects a specific part of the body and can influence things like our metabolism, blood sugar regulation, thyroid function, blood pressure, cardiovascular disease, male sex characteristics, libido, menstrual cycle, fertility, and mental health. This important gland plays a pivotal role in regulating the body’s functioning and our overall wellbeing.

SRR also has a strong focus on the Kidney /Adrenals, Brain Stem and other systems of the body including skin, digestive and musculo-skeletal ( fascia, muscle, bone) systems and more.

The Kidney Adrenal System

The kidney adrenal system is one of the direct pathways that allow us to work with and influence the nervous and endocrine systems. These direct pathways support us to tap into regulation. The adrenals, located on the kidneys can be found in our mid-back area. They are a major part of the sympathetic nervous system which acts to produce cortisol and norepinephrine (adrenaline), some of the key chemicals involved in the body’s threat response.

When we are under stress our kidney adrenals constrict and can move into over-drive. This makes it hard to experience a sense of calm and feel regulated when your adrenals are always pumping out stress hormones, as is the case for people those of us who have experienced developmental trauma, we have systems chronically set on high alert, that need extra support to move into more regulation. Additionally, we know that there are also many other life stressors in our modern world that can trigger our body's stress response and influence our bio-physiological health.

We know that stress hormones are important, and play an important part in motivating us and we need them to live. They are part of what gives us energy, keeps us alive and helps us respond in dangerous or stressful situations. However as discussed above, the challenge is that when we are exposed to chronic ongoing stress or trauma, our bodies will begin to secret these chemicals and the HPA axis is unable to ‘turn off’, which can leave us trapped in unresolved pastes of fight-flight and freeze physiology

.“Discharges [of stress chemicals] constitute the flight-or-fight reactions that help us survive immediate danger. These biological reactions are adaptive in the emergencies for which nature designed them. But the same stress responses, triggered chronically and without resolution, produce harm and even permanent damage. Chronically high cortisol levels destroy tissue. Chronically elevated adrenalin levels raise the blood pressure and damage the heart.” Dr. Gabor Mate

What Techniques are Used in Therapeutic Touch for Trauma Healing?

In the same way that an attuned, and present caregiver can bring a sense of calm to an infant or animal, a therapist that is trained in somatic touch work uses their own regulated nervous system to help bring regulation back to the client’s nervous system. This experience of co-regulation supports a person's nervous system to move into regulation rather than staying stuck in dysregulated states.

Using physical touch or intentional touch ( focused attunement) the presence of the therapist’s hand or focus supports the muscles in the area to relax and allows blood flow to increase. This experience of co-regulation also means that there is very little demand on a a body and nervous system that may be in allostatic overload. This is important as when we are in overload, any additional demands can feel overwhelming to the body.

One example is when the kidneys or kidney adrenal areas are held safely, the body can start to relax and shift more into a parasympathetic response. This helps to reduce the flow of stress hormones like cortisol, epinephrine, norepinephrine and adrenaline, sending the message to the brain that it’s ok to rest, helping the body to get a little circuit breaker in the constant experience of threat or unsafely.

Each time we do this it creates a little ripple of something new in a person’s nervous system, interrupting the release of those stores of hormones, which allows us to create a new experience, that tells your body, this is what safety feels like, and right now it’s safe. Over time and with repetition, the body can take in more and more regulation and healing. The reduction in the secretion of stress hormones means there is a shorter acting effect, and in 8-10 minutes your body can start to break down some of those stores hormones, interrupting the chronic overuse of the adrenal system that causes adrenal fatigue when these substances are not broken down and present all the time.

A similar process is used for the brain stem which is involved in hypervigilance and threat detection... Supporting the brain stem area reduces fear, alarm and hypervigilance. It can also stimulate and regulate feelings of well-being and safety.

In SRR work can also be done at the level of the skin, fascia (a layer just under the skin that can be tight, softening holds a lot of emotion ), muscle and bone, working to regulate these different levels of the body bringing these layers into balance. Working with the fascia can also reduce feelings of agitation and overwhelm.

Working with and healing developmental trauma means learning about what safety feels like. Often we have to learn how to do that. We have to re learn rest and relaxation to FEEL safe, rather than feeling safe to relax.

This includes feeling safe within ourselves, because again we have lived in places of either fight/flight agitation or shutdown and collapse, with no true experience of rest or settling. In nervous system terms, we say this is where the system alternates between high sympathetic tone until the dorsal vagal system sends it into shutdown. Kathy Kain points out that a milder signal, also known as low tone dorsal can promote digestion, immune function, cell repair, and reduction of inflammation.

This rest state is important in healing from chronic health conditions that often affect trauma survivors, as shown by the ACE study. When you can enter into low-tone dorsal states, whilst experiencing co-regulation your body can have the felt experience of safety and rest. This allows the body a pause from those states of fight, flight, freeze and collapse. The body has time to start to repair and we give the system a chance to recover from the allostatic overload. There is no demand being placed on the system and nothing in the environment or around you is signalling threat.

Below is a link to research studies on the SRR method, as well as sources of more information:

Two Experiments on the Psychological and Physiological Effects of Touching-Effect of Touching on the HPA Axis-Related Parts of the Body on Both Healthy and Traumatised Experiment Participants https://www.mdpi.com/2076-328X/8/10/95

A discussion of the ACES study, its findings and the impact of trauma on our health: The Deepest Well: Healing the Long-Term Effects of Childhood Adversity by Nadine Burke.

The appendix of Nurturing Resilience: Helping Clients Move Forward from Developmental Trauma

Additional resources at: Somaticpractice.com and Austinattach.com