Understanding Emotional Neglect

Understanding Emotional Neglect

What Is Emotional Neglect? How It Affects You and How NeuroAffective® (NAT) Touch Can Help

Understanding Emotional Neglect: The Hidden Wound and the Power of NeuroAffective® (NAT) Touch

Emotional neglect is an often-overlooked form of childhood adversity that profoundly influences a person’s emotional and psychological development. Unlike overt abuse, which involves active harm, emotional neglect is characterized by the absence of essential emotional support, validation, and nurturing during critical developmental periods. This lack of emotional attunement can lead to enduring challenges in emotional regulation, self-worth, and interpersonal relationships. Emerging therapeutic approaches, such as NeuroAffective Touch® (NAT), offer promising avenues for healing by addressing these deep-seated emotional wounds through the integration of touch in psychotherapy.

This blog article explores the nature of emotional neglect, its developmental impact, and the role of NeuroAffective Touch®in providing reparative experiences that address early attachment wounds.

What is Emotional Neglect?

Defining Emotional Neglect

Emotional neglect occurs when caregivers fail to respond adequately to a child's emotional needs. Unlike physical neglect, which manifests as a lack of food, shelter, or medical care, emotional neglect is insidious and difficult to identify. It is also different to abuse. When it comes to describing emotional neglect, there isn't something that somebody did, instead there is an absence, it's a deficit… and it's always more difficult to point to and talk about something that isn’t there than something that is there. Because emotional neglect is an absence rather than an act, making it can be particularly challenging for people who have experienced it to recognize and name their experience.

Emotional neglect can manifest in different ways including:

Parental Emotional Neglect: When caregivers are emotionally unavailable, unresponsive, or dismissive of a child's feelings, it can lead us to feel a sense of unworthiness and invisibility.

Cultural or Collective Neglect: Societal norms or cultural practices that devalue emotional expression can contribute to a collective form of neglect, where individuals learn to suppress their emotions to conform to expectations.

Medical or Systemic Neglect: Within healthcare or institutional settings, the absence of empathetic communication and emotional support can lead to feelings of isolation and abandonment, exacerbating an individual’s distress.

How Emotional Neglect Affects Identity Formation

Children who experience emotional neglect often develop insecure attachment styles. These attachment patterns shape how a child then perceives relationships, trusts others, and manages emotions. Common traits seen in adults who were emotionally neglected include:

Difficulty identifying their emotions: People who have experienced neglect often struggle to name what they feel, as their emotional world was never consistently mirrored back to them or validated by a care giver.

A pervasive sense of emptiness: Because neglect is an absence of something. A person might not have a sense of what’s missing in their lives, but they often feel deep sadness or emptiness without a ‘reason’.

Chronic self-doubt: An internalized belief that their needs and feelings do not matter, leading to a diminished sense of self-worth. This makes sense because children make meaning of their needs not being attuned to, and the meaning becomes there must be something wrong with me, it must be my fault. If only I was different, better or more in some way.

Fear of intimacy or deep connection: Since caregivers failed to provide emotional warmth, relationships may feel unsafe or overwhelming, there is no experience of closeness and connection and thus no experience of nurturing or nourishment from relationship.

Emotional Neglect and It’s Impacts on our Core Needs

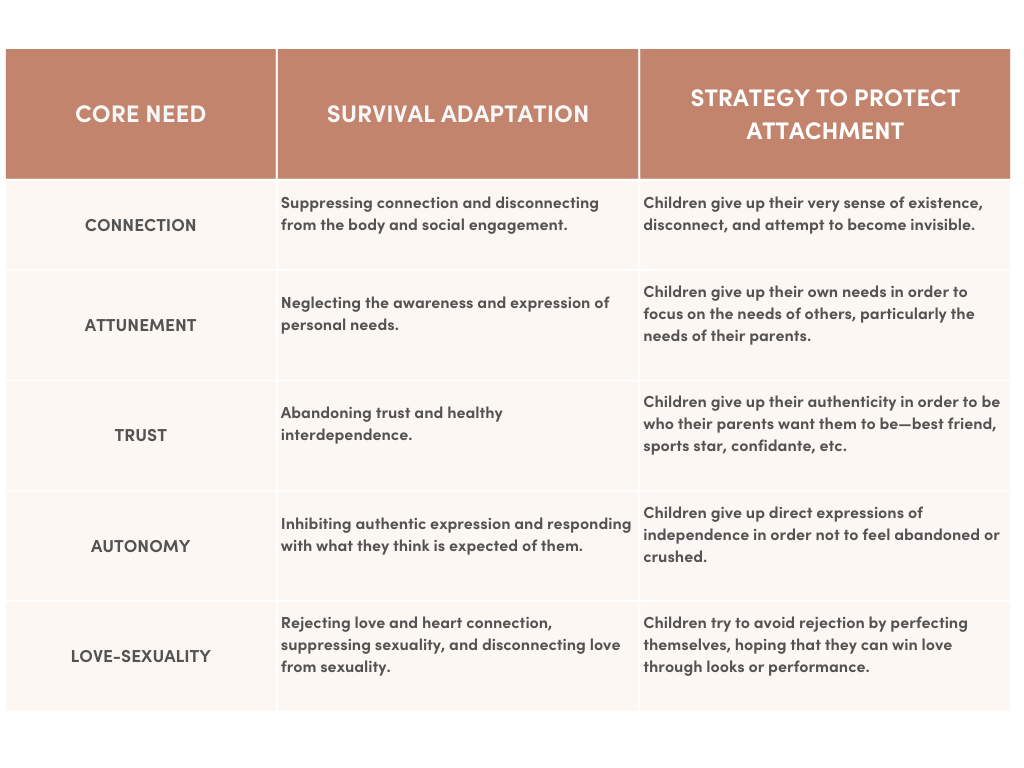

Emotional neglect impacts our core needs around: connection, attunement, trust,autonomy, love and sexuality.

The need for Connection: When our need for connection ins not met, this leads to the survival strategy of supressing connection and disconnecting from the body and social engagement. The behaviors used as a strategy to protect the attachment relationship look like: Children give up their very sense of existence, disconnecting, and attempting to become invisible. It may feel like they don’t have a right to exist or even that they don’t exist.

HERE’S AN EXAMPLE OF THE UNMET NEED FOR CONNECTION

Scenario:

Emma grew up in a household where emotions were dismissed. When she expressed sadness or excitement, her parents responded with indifference or criticism. To protect herself, she learned to suppress her emotions and became hyper-independent.

Adult Manifestation:

Now in her 30s, Emma struggles to form close relationships. She avoids intimacy, feeling uncomfortable when people get too close. At work, she is highly competent but emotionally distant. In romantic relationships, she often feels disconnected, as if she’s watching her life from the outside. She tells herself she doesn’t need anyone, but deep down, she longs for closeness and fears abandonment.

The need for Attunement: When our need for attunement is not met, this leads to the survival strategy of supressing the awareness and expression of personal needs. The behaviors used as a strategy to protect the attachment relationship look like: Children will give up their own needs in order to focus on the needs of others, particularly the needs of their parents.

HERE’S AN EXAMPLE OF THE UN MET NEED FOFR ATTUNEMENT

Scenario:

Jake’s parents micromanaged every aspect of his life. They chose his clothes, dictated his hobbies, and dismissed his opinions. When he tried to make decisions, he was told he’d “mess it up.”

Adult Manifestation:

Now, Jake finds it hard to make even simple decisions without reassurance from others. He second-guesses himself at work, afraid of making mistakes. In relationships, he is overly accommodating, fearing that asserting himself will push people away. He dreams of starting his own business but believes he isn’t capable of success.

The need for Trust: When our need for trust is not met, this leads to the survival strategy of supressing trust and healthy interdependence. The behaviors used as a strategy to protect the attachment relationship look like: Children giving up their authenticity in order to be who their parents want them to be. they may become their best friend, the sports star, confidante or any other role that the parent wants the child to play.

Adapted form the book Healing developmental trauma By Larry Heller and Aline Lapierre

HERE’S AN EXAMPLE OF THE UN MET NEED FOFR TRUST

Scenario:

Ava grew up with parents who made promises they never kept. Her mother frequently said she would pick her up from school but often forgot, leaving Ava waiting for hours. Her father would promise to take her to the park but would cancel at the last minute. Over time, Ava learned she couldn’t rely on anyone and that trusting others would only lead to disappointment.

Adult Manifestation:

As an adult, Ava finds it difficult to trust people. In relationships, she expects betrayal and frequently accuses her partner of being dishonest, even without evidence. At work, she micromanages her team, convinced that if she doesn’t control everything herself, it will fall apart. Ava is hyper-independent and refuses to ask for help, believing it’s safer to do everything alone. Though she craves deep connection, her inability to trust others leaves her feeling isolated and lonely.

The need for Autonomy: When our need for autonomy is not met it leads to the survival strategy of suppressing authentic expression and responding with what they think is expected of them. The behaviors used as a strategy to protect the attachment relationship look like: Children giving up direct expressions of independence in order not to feel abandoned or crushed.

HERE’S AN EXAMPLE OF THE UNMET NEED FOR AUTONOMY

Scenario:Jake’s parents micromanaged every aspect of his life. They chose his clothes, dictated his hobbies, and dismissed his opinions. When he tried to make decisions, he was told he’d “mess it up.”

Adult Manifestation:

Now, Jake finds it hard to make even simple decisions without reassurance from others. He second-guesses himself at work, afraid of making mistakes. In relationships, he is overly accommodating, fearing that asserting himself will push people away. He dreams of starting his own business but believes he isn’t capable of success.

The need for Love-Sexuality: When our need for love or expression of sexuality is not met, leads to the survival strategy of suppressing love and heart connection, sexuality, and the integration of love with sexuality. The behaviors used as a strategy to protect the attachment relationship look like: Children trying to avoid rejection may do so by trying to perfect themselves, hoping that they can win love through the way they look or their performance.

HERE’S AN EXAMPLE OF THE UNMET NEED FOR LOVE-SEXUALITY

Scenario:

Daniel grew up in a home where affection was either completely absent or only given as a reward for good behavior. His parents rarely hugged him or expressed love, and when they did, it felt transactional—“If you behave, then you get a hug.” As he entered adolescence, any conversations about relationships or sexuality were avoided or met with shame. He learned that love had to be earned and that physical closeness was either unimportant or inappropriate.

Adult Manifestation:

Now in his 30s, Daniel struggles with romantic relationships. He feels emotionally detached and avoids vulnerability, believing that love must be "deserved" through achievement or perfection. In some relationships, he is hypersexual, using physical intimacy as a way to feel momentarily connected—only to feel empty afterward. In others, he avoids sex altogether, feeling shame or discomfort with physical closeness. Deep down, he fears that if someone truly sees him, they will find him unworthy of love.

Emotional Neglect and the Nervous System

Research suggests that early emotional deprivation has profound effects on brain development, particularly in the regions responsible for emotional regulation and social bonding. Teicher et al. (2016) found that emotional neglect alters the trajectories of brain development, leading to structural and functional impairments in the prefrontal cortex, amygdala, and hippocampus (Teicher et al., 2016). Additionally, people with a history of emotional neglect often exhibit dysregulation in the autonomic nervous system, meaning they may live in states of hyperarousal (chronic anxiety) or hypoarousal (emotional numbness). It is also common that adults who have experienced emotional neglect as children feel a sense of social anxiety, of shyness and often of shame. There can be a sense of awkwardness socially because true connection in relationship was missing.

Neglect is about being ignored and not being attuned to. It is a feeling of not having the sense that we’re really important to anyone, we might wonder why someone would care for us or find it hard to believe that someone would find us worthy of love. This feeling of somehow fundamentally not belonging or not understanding why someone would want to care about you often shows up more as a strong inner feeling, without many words to effectively describe it. This highlights how neglect imprints itself deeply within an individual's nervous system, making it difficult to recognize or verbalize the emotional deprivation a person has experienced.

Why Touch Matters in Healing Emotional Neglect

Touch is one of the earliest ways humans communicate and form secure attachments. We know from research that touch boosts serotonin, increases blood flow to the brain, reduces blood pressure, bolsters our immune system, improves brain cognition, and fights inflammation. It also plays a fundamental role in:

Regulating the nervous system: Gentle, attuned touch can help modulate the autonomic nervous system, promoting relaxation and reducing hyperarousal states.

Fostering secure attachment: Through therapeutic touch, individuals can experience a sense of safety and connection, facilitating the development of new attachment patterns.

Accessing implicit memories: Many effects of emotional neglect are stored as implicit, bodily-held memories. Touch-based interventions can help access and process these non-verbal imprints.

Enhancing self-awareness: Touch can bring attention to bodily sensations, fostering greater self-awareness and helping individuals reconnect with their physical selves.

NeuroAffective Touch® and Its Impact on Emotional Neglect

NeuroAffective Touch® (NAT) is an integrative somatic therapy that incorporates attuned touch into psychotherapy. According to LaPierre (2018): NeuroAffective Touch® addresses emotional, relational, and developmental deficits that cannot be reached by verbal means alone.” (LaPierre, 2018) Since emotional neglect primarily affects non-verbal, pre-verbal, and autonomic nervous system regulation, verbal psychotherapy alone may not be sufficient for deep healing. NAT provides a direct sensory experience of attunement and care, helping clients develop new somatic and relational patterns. Touch can be the vehicle that communicates the missing messages: You are wanted and you are welcome in the world.

How NeuroAffective Touch® Helps Rewire the Nervous System

NAT engages the body's natural mechanisms for healing through:

Slow, regulated touch to create safety.

Somatic resourcing techniques to enhance interoception (awareness of internal body states).

Grounding exercises that counteract the dissociative effects of neglect.

Gentle holding techniques to provide a corrective relational experience.

When a person has been neglected they may not know what to do with relational engagement. They need slow, regulated exposure to touch so they can rewire their nervous system. A 2019 study on body-based psychotherapy found that somatic interventions significantly improved emotional regulation in individuals with complex trauma histories (Ogden et al., 2019). These findings support the premise that touch-based therapies, like NAT, can be instrumental in addressing developmental trauma.

Advanced Applications of NeuroAffective Touch® for Healing Emotional Neglect

Why Traditional Talk Therapy Falls Short in Addressing Emotional Neglect

Traditional psychotherapy, while invaluable in many ways, is often insufficient when it comes to healing emotional neglect. Since neglect is pre-verbal and implicit, it leaves imprints in the nervous system that cannot always be accessed through cognitive processing alone. This is why we say, words are not enough.

As discussed, because neglect is about absence a person won’t necessarily know what’s missing in their lives, they wont know how to ask for what they have never received and they also won’t know necessarily know what they need or what’s possible for them. Instead, this all too common experience of lack, and the absence of attuned responses in childhood creates developmental gaps, leaving people struggling to recognize and articulate their emotional needs.

They may often start therapy thinking or saying:

"I don’t know what I feel."

"I have a deep sadness/ I just feel sad all the time, but I don’t know why."

"I always feel like something is missing, but I can't name it."

Splitting, Emotional Neglect, and the Role of NAT in Integration

While NAT effectively addresses the nervous system dysregulation caused by emotional neglect, it also plays a crucial role in helping clients integrate split-off emotional experiences. Splitting is a common defense mechanism for individuals who grew up in neglectful environments, where emotional attunement was inconsistent or absent. To understand how NAT can help reintegrate these fragmented emotional experiences, we must first explore the phenomenon of splitting and its impact on emotional regulation.

Understanding Splitting and Emotional Neglect

Splitting is a psychological defense mechanism that arises when a person cannot hold opposing emotions or perspectives simultaneously. It often develops in response to inconsistent emotional attunement during childhood, particularly in emotionally neglectful environments. Children who experience emotional deprivation learn to divide their reality into extremes—good vs. bad, safe vs. unsafe, loved vs. abandoned—because their nervous systems lack the regulation needed to process nuance.

When emotional neglect is present, a child might split off painful emotions or even split their sense of self into acceptable and unacceptable parts to maintain an attachment to their caregiver. Over time, this habit of splitting becomes ingrained, making it difficult for adults to integrate complex emotional experiences without resorting to either emotional repression or emotional outbursts.

Example of Splitting as a Coping Mechanism in Childhood

Imagine a child growing up in an emotionally neglectful home who receives love and approval only when they are quiet, helpful, or achieving, but are ignored or criticized when they express anger, sadness, or neediness, they may learn to see certain parts of themselves as "good" and others as "bad."

To cope, the child unconsciously rejects their "bad" emotions—perhaps becoming overly responsible, people-pleasing, or emotionally numb, while hiding or disowning their anger, sadness, or vulnerability. Over time, this splitting helps them survive in their home but makes it difficult to integrate all aspects of themselves as they become an, leading to struggles with self-worth, emotional regulation, and authentic self-expression in adulthood.

Acting ‘In’ or Acting ‘Out’

Emotional neglect can lead to two primary coping strategies: acting out or acting in. While some individuals suppress their emotions and turn them inward (acting in), others externalize their distress through anger, avoidance, or emotional outbursts (acting out). This is not a conscious choice but a survival adaptation—a way the nervous system attempts to manage overwhelming feelings without internal tools for regulation. A clear example of this can be seen in parents who were emotionally neglected as children and struggle with emotional triggers in their own parenting experiences. The following case study illustrates how acting out can manifest in adulthood.

Case Study: A Father Triggered by His Child’s Crying, “Acting Out”

Splitting is often seen in parents who were emotionally neglected themselves, leading them to react intensely to their child's emotional needs—either rejecting them or over-identifying with them.

James, a 38-year-old father, came to therapy feeling deeply ashamed of his reactions to his 2-year-old son. Whenever his son cried, James felt a surge of anger, followed by overwhelming guilt. He described his response as "automatic," as if his body was being hijacked by emotions he couldn’t control.

Because the body predicts outcomes based on past experiences, and when the past is full of neglect, it predicts that expressing emotions is dangerous. When James’ son cried, his unprocessed childhood emotions resurfaced, activating a fight-or-flight response that made him want to shut his child down the same way he had been shut down. This reaction was not a conscious choice but a somatic memory stored in his nervous system.

Through exploration in therapy, James realized that as a child, his own emotions had been met with silence or punishment. His parents discouraged emotional expression, often telling him, “Crying won’t solve anything” or “Be a man and toughen up.” As a result, he split off his vulnerable, emotional self to survive childhood. What was coming up under the anger was fear. Understanding that underneath the anger was fear, was a big step in helping James begin respond differently in the moment and work with his own emotional responses and unmet needs that were bring triggered.

Splitting and the Fight/Flight/Freeze Response

Splitting is deeply connected to the nervous system’s survival responses:

Fight: The individual reacts aggressively to perceived emotional threats, often becoming critical or dismissive.

Flight: The person avoids emotional closeness, keeping relationships at a surface level.

Freeze: Emotional numbing occurs, making it difficult to feel or express emotions.

In James' case, his fight response was activated when his son cried, but it was quickly followed by freeze, where he would dissociate and withdraw emotionally.

Case Study: Anna, 34 – Internalizing Emotional Neglect Through Self-Criticism ("Acting In")

Anna, a 34-year-old marketing executive, sought therapy due to persistent self-criticism and chronic feelings of unworthiness. Although outwardly successful, she struggled with an inner voice that constantly told her she wasn’t good enough. She was high-achieving but exhausted, and no amount of external validation seemed to relieve her deep-seated sense of inadequacy.

Through therapy, Anna uncovered that as a child, her emotions were consistently ignored. When she expressed sadness or distress, her parents either dismissed her feelings ("You’re too sensitive") or compared her to others ("Why can’t you be more like your cousin?"). Over time, she learned that expressing her emotions led to rejection, so she turned her frustration and pain inward, blaming herself rather than acknowledging the neglect she had experienced.

Children internalize their environment. If no one responds to their distress, they believe it’s their fault and develop a harsh inner critic to compensate for the lack of external attunement. This protects the attachment relationship with their caregiver and helps a child make meaning. Blaming themselves also brings some way to try and control or change what is happening, because if it is your fault, you can try and do something about that. taking on this belief comes at a heavy cost.

Anna’s “acting in” manifested as:

Perfectionism – She constantly pushed herself to perform flawlessly, believing that if she could just be perfect, she might finally feel worthy.

Over-functioning in relationships – She prioritized the needs of others above her own, struggling to express what she truly wanted.

Emotional numbing – Whenever she felt sad or overwhelmed, she shut down her emotions instead of allowing herself to process them.

Self-criticism and shame – Her internal dialogue was harsh and unforgiving, mirroring the emotional neglect she had experienced in childhood.

Splitting and Internalized Shame ("Acting In")

Anna’s case illustrates a different form of splitting, where instead of projecting emotional distress outward (acting out), she turned it inward against herself. This left her trapped in a cycle of self-blame and self-denial, reinforcing the false belief that she was unworthy of care or emotional expression. When a child learns that their needs are unwelcome or inconvenient, they disconnect from those needs and believe they must earn their right to exist by performing or pleasing others..

How NAT Helps Heal Splitting

NeuroAffective Touch® (NAT) plays a crucial role in reintegrating split-off emotional parts by:

Providing Safe Co-Regulation: By receiving attuned, gentle touch, clients can experience safety in the body, making it easier to process emotions without needing to split them into "good" or "bad."

Engaging Implicit Memory Systems: NAT helps access pre-verbal, body-stored trauma, allowing clients to process the origins of their emotional triggers.

Integrating Opposing Emotions: Instead of reacting with anger or shutdown, clients learn to hold both discomfort and connection simultaneously, reducing black-and-white emotional responses.

NeuroAffective Touch® as a Somatic Bridge for Healing

NeuroAffective Touch® (NAT) helps bridge this gap by directly engaging the body's implicit memory system. Through gentle, relational touch, therapists help clients develop a felt sense of presence, something they may have never experienced in their early attachment relationships. LaPierre (2022) explains:“Healing from neglect requires more than insight; it requires an embodied experience of presence and attunement that was missing in the past.” (LaPierre, 2022) Since touch activates the limbic system—the part of the brain responsible for emotional regulation, clients can experience new relational imprints that help rewire early deficits in emotional attunement.

Key Techniques in NeuroAffective Touch® for Neglect Healing

1. Gentle, Containment-Based Touch

Individuals who have experienced neglect often feel disembodied—disconnected from their physical selves. One powerful technique in NAT involves using soft, weighted objects (e.g., warm pillows, weighted blankets) to mimic the missing sense of holding and containment. This helps create a feeling of safety in the body before progressing to deeper work.

A study by Montagu (1986) found that touch is essential for healthy brain development, as it stimulates the production of oxytocin, the hormone linked to attachment and trust (Montagu, 1986). This aligns with research on Polyvagal Theory, which highlights how co-regulation through safe touch can help shift the nervous system from survival states into connection (Porges, 2011).

2. Breath and Somatic Awareness to Counter Dissociation

People who have been neglected frequently dissociate from their bodies. There is often high levels of fear and many people will often share that they are afraid, they don’t not know why they're afraid, but they feel afraid all the time.

In NAT, therapists may use breathwork and grounding exercises to help clients become more aware of bodily sensations. This may involve:

Guided breathing techniques to anchor clients in the present.

Hand placements on the heart or abdomen to encourage self-soothing.

Movement-based interventions such as stretching to restore a sense of vitality.

These techniques are particularly effective for clients with hypoarousal, who may feel emotionally flat or disconnected. Research by Ogden et al. (2006) reflects this as it found that somatic interventions improve affect regulation in trauma survivors, making them highly relevant for individuals with neglect histories.

3. Repairing the Early Attachment Blueprint

Neglect survivors often lack an internalized sense of “being held”—a fundamental aspect of secure attachment. According to Schore (2012): “The right hemisphere, which governs attachment and affect regulation, is shaped by early relational experiences.” (Schore, 2012) Bowlby’s Attachment Theory (1988) supports this, stating:“Early attachment experiences shape an individual’s capacity for intimacy and emotional regulation throughout life.” (Bowlby, 1988)

NAT provides corrective relational experiences that repair the early attachment blueprint. This involves attuned touch in a structured, consent-based manner, allowing clients to re-experience what it feels like to be seen, heard, and held. Over time, these experiences rebuild a sense of safety and increase the client’s capacity for emotional intimacy.

Integrating NeuroAffective Touch® with Other Therapeutic Modalities

NeuroAffective Touch® (NAT) is can be very effective when integrated with complementary therapeutic approaches that target both body-based and cognitive processing. Emotional neglect is not just a psychological experience; it is also deeply embodied, requiring interventions that work at multiple levels. This section explores how Polyvagal Theory, Somatic Experiencing, and Mindfulness-Based Interventions can enhance NAT’s effectiveness.

1. Polyvagal Theory: Regulating the Nervous System Through Touch

Polyvagal Theory (Porges, 2011) provides a framework for understanding how the nervous system responds to safety, connection, and threat. It identifies three key states:

Ventral Vagal (Safe & Social State) – When regulated, individuals feel connected, safe, and engaged.

Sympathetic (Fight or Flight State) – When triggered, individuals may experience anxiety, hypervigilance, or agitation.

Dorsal Vagal (Shutdown State) – A state of freeze, numbness, or dissociation, common in those with emotional neglect histories.

NAT helps clients retrain their nervous system to experience safety by integrating attuned touch and co-regulation. Because neglect imprints dysregulation in the nervous system, leading to chronic disconnection, relational touch, NAT supports clients in shifting toward ventral vagal regulation—the state of safety and connection.

Techniques Using Polyvagal Theory in NAT

Hand placements on the upper back or chest to signal safety and regulation.

Rocking or rhythmic touch interventions to mimic the soothing effect of an attuned caregiver.

Co-regulated breathing practices to help synchronize nervous system states.

Porges (2017) explains:“Safe, attuned touch activates the parasympathetic nervous system and fosters neuroception of safety, allowing the client to engage more fully in therapy.” Research by Dana (2018) further supports this:“Polyvagal-informed therapy emphasizes creating an environment where the nervous system can shift from defense to connection.”

2. Somatic Experiencing (SE): Releasing Stored Trauma

Developed by Peter Levine (1997), Somatic Experiencing (SE) focuses on discharging trapped survival energy from past trauma. Since emotional neglect creates a freeze response, many survivors remain stuck in a state of hypoarousal, unable to fully engage with life.

This makes sense because neglect is not an event—it’s a persistent absence. And in that absence, we find a deep void. NAT combined with SE can help resolve this feeling of a void by reintroducing safe somatic experiences. Clients often report feeling “frozen” or emotionally distant, reflecting a dorsal vagal state. SE techniques help them complete unprocessed survival responses and restore movement and aliveness.

Somatic Experiencing Techniques in NAT

Pendulation: Guiding the client between states of numbness and micro-movements to restore sensation.

Titration: Introducing small doses of touch to help regulate overwhelming emotions.

Interoceptive Awareness: Helping clients track internal sensations before and after touch interventions.

Research by Ogden, Minton, & Pain (2006) confirms: “Somatic regulation is essential in working with developmental trauma, as the body stores memory in implicit, sensory-based patterns.”

Levine (2010) expands on this: “Trauma is not just stored in the mind—it is embedded in the body. The only way to release it is through safe, controlled somatic experiences.”

3. Mindfulness-Based Interventions: Strengthening the Mind-Body Connection

Mindfulness-based therapies, including Mindfulness-Based Stress Reduction (MBSR) and Mindful Self-Compassion (MSC), complement NAT by fostering greater internal awareness and acceptance.

A primary challenge for individuals with emotional neglect is difficulty staying present with emotions. Many describe:

Feeling disconnected from their body.

Engaging in chronic self-criticism.

Struggling with shame-based narratives that stem from a lack of early attunement.

Adults who were ignored as children have an inner critic that tells them they are at fault. They learn to mask their deep depletion by striving for external validation. Mindfulness can help addresses this by helping clients observe their thoughts without judgment and develop self-compassion.

Mindfulness Techniques in NAT

Body scans combined with light touch interventions to increase awareness.

Breath-focused grounding techniques to cultivate present-moment awareness.

Loving-kindness meditations to counteract the internalized shame of neglect.

Neff & Germer (2013) emphasize: “Self-compassion counteracts the lasting effects of childhood emotional neglect by providing the internal attunement that was missing in early years.”

Practical Applications of NeuroAffective Touch® in Clinical Settings

While NeuroAffective Touch® (NAT) is a powerful intervention for addressing emotional neglect, its effectiveness is maximized when implemented thoughtfully and ethically. This section provides guidance for therapists on best practices, client-centered approaches, session structure, and common challenges encountered when incorporating NAT into trauma therapy.

Guidelines for Therapists Using NAT

Therapists integrating NAT into their practice must be mindful of client consent, attunement, and ethical considerations. Unlike talk therapy, where verbal engagement is the primary tool, NAT involves direct physical engagement, which must always be done within clear therapeutic boundaries.

Ethical Considerations

Informed Consent: Clients must be fully informed about the role of touch in therapy, including what it entails and their right to withdraw consent at any time.

Cultural Sensitivity: Some clients may have cultural or personal barriers around physical touch. Practitioners must be aware of cultural norms and engage in discussions about comfort levels.

Trauma Awareness: For survivors of physical or sexual trauma, touch can be triggering. Gradual, titrated introduction of NAT techniques is essential to avoid re-traumatization.

When a person with neglect comes into our treatment room, it’s very scary for them because this is a brand-new experience. Other humans have not been a source of comfort and thus cannot yet be trusted to provide comfort or support. According to Zur and Nordmarken (2011): “Ethical use of touch in psychotherapy must be grounded in attunement, clear consent, and continuous client feedback.”

Client-Centered Approaches in NAT

Each person has unique needs based on their attachment history, trauma experiences, and emotional regulation patterns. NAT must be tailored to the individual, considering factors such as attachment style, nervous system state, and level of body awareness.

Working with Different Attachment Styles

Avoidant Attachment: Physical closeness can feel very difficult for people who identify with having an avoidant attachment, due to early neglect or rejection. Introducing NAT slowly, through indirect touch interventions (e.g., weighted blankets, grounding exercises), helps create a sense of safety.

Anxious Attachment: People who experienced inconsistent caregiving may crave but also fear touch. NAT can support boundary-setting exercises alongside physical attunement to foster security.

Disorganized Attachment: People who identify with disorganized attachment may experience conflicting responses to touch, making polyvagal-informed regulation techniques essential before introducing direct NAT interventions.

Adults ignored as children can struggle with feeling welcome anywhere. They do not feel like they belong, and often, this is deeply ingrained in how we engage in relationships. Siegel (2012) explains: “Attachment-based interventions must account for implicit body memories and relational conditioning, as these shape the nervous system’s response to touch.”

Structure of a NeuroAffective Touch® Session

A typical NAT session follows a structured yet flexible format, ensuring safety, regulation, and integration. Below is an example outline of how an NAT session may be conducted:

Session Phases:

Opening & Safety Check-In (10 minutes)

Assess the client’s nervous system state (e.g., hyperarousal, hypoarousal, dissociation).

Utilize grounding techniques (breathwork, mindful tracking, verbal check-in).

Reaffirm client agency (e.g., “At any moment, you can pause or change the intervention.”)

Somatic Engagement & Touch-Based Interventions (30-35 minutes)

Apply gentle, consent-based touch (e.g., hand on back, weighted object placement).

Incorporate movement-based NAT techniques (e.g., gentle rocking, proprioceptive input).

Use guided somatic awareness to help clients track body sensations.

Integration & Verbal Processing (15 minutes)

Encourage reflection on body sensations and emotions post-touch intervention.

Engage in narrative integration, allowing clients to verbalize any emerging themes.

Close with a self-soothing practice (breathwork, visualization, or a stabilizing movement).

Research by Ogden & Fisher (2015) suggests: “The integration phase is as important as the intervention itself, ensuring clients process and store new sensory experiences in a regulated manner.”

Challenges and Considerations in NAT

While NAT is highly effective, certain challenges may arise, particularly for clients who have never experienced safe touch. Below are common concerns and considerations to address them:

Some people may feel uncomfortable with direct touch due to trauma history.

Instead of direct touch we can use intentional touch ( holding intention and focus rather than physical touch). We can also introduce symbolic touch (e.g., wrapping in a blanket, using warm objects) before progressing to direct interventions.

Some people may experience dissociation when engaging in body-based interventions. We can use titration, or small experiences that begin with short, contained touch experiences to prevent overwhelm.

Some people may experience strong emotional releases after receiving attuned touch as well as people may struggle with allowing themselves to receive care. We can take time and titrate the experience. We may build resources around breathwork and grounding techniques to promote regulation.

Levine (2015) explains: “For trauma survivors, the process of receiving safe, attuned touch can be both healing and challenging. Pacing and containment are crucial.”

Research and Applications of NeuroAffective Touch® in Trauma Therapy

NeuroAffective Touch® (NAT) has revolutionized trauma therapy by addressing the non-verbal, somatic imprints of emotional neglect. This section explores the scientific research, physiological mechanisms, and real-world applications of NAT, expanding on how it helps clients heal from developmental trauma.

Scientific Research Supporting NAT in Trauma Healing

NeuroAffective Touch® operates at the intersection of neuroscience, attachment theory, and somatic therapy, making it particularly effective for treating emotional neglect. We know there is a potent biological connection between touch and the brain. Touch improves blood flow, increases serotonin, and fosters a sense of being held. The following research findings highlight NAT’s impact:

Neurobiology of Touch and Healing: Studies show that affective touch activates the insular cortex, which is responsible for interoception and emotional awareness (McGlone et al., 2014).

Polyvagal Theory and Touch: Porges (2017) found that attuned, gentle touch activates the vagus nerve, shifting the nervous system from survival states (fight/flight) to connection (ventral vagal activation)

Attachment Repair: Research by Cozolino (2014) indicates that co-regulation through touch strengthens the right hemisphere of the brain, which governs relational safety and emotional attunement.

Reduction in Cortisol and Increase in Oxytocin: Field (2010) documented that therapeutic touch reduces stress hormone levels while increasing oxytocin, the “bonding hormone” essential for trust and relational security.

Physiological Mechanisms of NAT in Healing Emotional Neglect

Emotional neglect affects the nervous system, often leaving individuals chronically dysregulated. NAT works by retraining the body’s regulatory systems, particularly in these areas:

Regulating the Autonomic Nervous System

Emotional neglect disrupts autonomic balance, leaving individuals in states of hypervigilance (anxiety) or hypoarousal (dissociation).NAT’s slow, rhythmic touch signals safety, engaging the parasympathetic nervous system to promote relaxation.Rebuilding Emotional Memory Through Touch

The absence of nurturing touch in early life leaves gaps in emotional memory. NAT reintroduces safe, attuned contact, helping the brain recreate and integrate missed relational experiences.Improving Interoception and Emotional Awareness

Clients with neglect histories often lack body awareness, struggling to identify sensations or emotions. NAT enhances interoception (the ability to sense internal bodily states), allowing clients to reconnect with their physical and emotional selves.

Theoretical Foundations Supporting NAT

While research on nurturing affective touch (NAT) as a specific intervention is still emerging, foundational studies in somatic therapy, self-compassion, and interpersonal neurobiology provide strong support for the mechanisms underlying its benefits. Ogden & Fisher (2015) highlight the role of somatic interventions in trauma recovery, particularly in reducing dissociation and hypervigilance, both of which are common in individuals with emotional neglect. Neff & Germer (2013) demonstrate that self-compassion practices, which can include gentle self-touch, enhance emotional resilience and self-regulation.

Similarly, Cozolino (2014) emphasizes the importance of attachment and co-regulation in shaping emotional well-being, reinforcing the idea that safe, attuned interactions—whether through relational or sensory experiences—support nervous system regulation. Schore’s (2012) work on right-brain development and affect regulation further underscores the role of early attunement in emotional processing, suggesting that body-based interventions may help repair attachment disruptions.

While these studies do not focus exclusively on NAT, they provide a strong theoretical foundation for understanding why nurturing touch can be a powerful tool in emotional neglect recovery. Emerging research on affective touch(pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov) and therapeutic touch-based interventions (pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov) further strengthens this perspective, highlighting its potential to promote safety, connection, and regulation in individuals with developmental trauma. Additionally, attachment-focused touch therapies, such as Transforming Touch®, have been developed to help individuals recover from early relational trauma (austinattach.com).

Integrating NAT into therapeutic practices offers a somatic pathway to repair attachment wounds, enhance self-regulation, and cultivate a deeper sense of connection, thereby addressing the multifaceted challenges associated with emotional neglect.Final

Summary and Key Takeaways

NeuroAffective Touch® (NAT) offers a groundbreaking approach to healing emotional neglect, addressing the non-verbal, somatic imprints that traditional talk therapy often overlooks. This final section summarizes the core findings, applications, and the future of NAT in trauma therapy.

Recap of Emotional Neglect & Its Impact

Emotional neglect is a persistent absence of attunement, warmth, and validation in childhood, leading to:

Difficulty identifying emotions and needs.

Dysregulation of the autonomic nervous system, resulting in chronic hypervigilance or dissociation.

Attachment wounds, where individuals struggle with intimacy, trust, and relational safety.

A pervasive sense of “not belonging”, affecting self-worth and social engagement.

Because neglect is absence, a person won’t always know what’s missing in their lives. They won’t know what’s possible for them. They are habituated to lack and may be more familiar with not receving or feeling like not having or having less than or nothing is normal.

Neglect is often preverbal, meaning that individuals may not have conscious memories of it but will experience an underlying sense of emptiness, disconnection, and longing. It’s a strange emptiness. It’s a void. When neglect shows up, it shows up as an emptiness and a void.

How NAT Addresses Emotional Neglect

Unlike talk therapy, which relies on cognitive processing, NAT directly engages the body’s regulatory systems. Key mechanisms include:

Regulating the nervous system through slow, attuned touch, activating the parasympathetic response.

Reintroducing safe relational contact, helping to rewire early attachment wounds.

Enhancing interoception, allowing clients to recognize and name bodily sensations and emotions.

Co-regulation, where attuned touch provides the missing experience of relational warmth and connection.

Schore (2012) explains:“The right hemisphere, which governs affect regulation, is shaped by early relational experiences and must be engaged through non-verbal interventions.” NAT helps clients re-engage with their body and others through touch, attuned presence, and structured safety exercises.

Major Research Findings Supporting NAT

There is a potent biological connection between the arts and the brain. So we know from research that it boosts serotonin, it increases blood flow to the brain, it reduces blood pressure, it bolsters our immune system, improves brain cognition, and fights inflammation.

Scientific research highlights NAT’s effectiveness:

Neuroscience of Touch: Affective touch activates the insular cortex, improving interoception and emotional regulation (McGlone et al., 2014).

Attachment Repair: Co-regulation through touch strengthens right-hemisphere connectivity, supporting relational healing (Cozolino, 2014).

Polyvagal Theory & Safety: Gentle, attuned touch activates the vagus nerve, reducing stress and increasing social engagement (Porges, 2017).

Hormonal Shifts: Therapeutic touch reduces cortisol and increases oxytocin, fostering emotional bonding (Field, 2010).

NAT works by stimulating these same biological pathways, reinforcing safety and connection.

Key Applications for Therapists & Clients

For Therapists:

Use NAT to support nervous system regulation in clients with complex trauma.

Introduce touch gradually, using weighted blankets or indirect methods before direct interventions.

Combine NAT with other modalities, such as Somatic Experiencing (SE), Mindfulness-Based Therapy, and EMDR.

For Clients:

Practice self-touch techniques (e.g., placing a hand over the heart) to build self-soothing skills.

Engage in breathwork and grounding exercises to reinforce NAT’s benefits outside therapy.

Develop awareness of bodily sensations, tracking changes in response to therapeutic interventions.

The Future of NAT in Trauma Therapy

As somatic-based interventions gain wider acceptance, NAT is becoming an essential part of trauma-informed care. Future directions include:

Expanding research on NAT’s efficacy in treating complex PTSD and attachment trauma.

Training more clinicians in touch-based therapy, ensuring ethical and attuned implementation.

Developing integrative models that combine NAT with cognitive-based therapies.

NAT offers an alternative pathway for individuals who struggle to put their experiences into words, allowing healing through felt experiences instead of verbal processing alone.

Final Thoughts

NeuroAffective Touch® is more than a technique—it is a paradigm shift in trauma healing. By integrating touch, relational attunement, and nervous system regulation, NAT offers a pathway to deep, embodied healing for those affected by emotional neglect. For therapists and clients alike, NAT represents a bridge to reconnection, offering what was missing in early development: safety, warmth, and the experience of being fully seen and held. Healing from neglect requires more than insight; it requires an embodied experience of presence and attunement that was missing in the past.