What Is Complex Trauma?

Trauma Counselling Brisbane

Natajsa Wagner Psychotherapy provides trauma informed counselling and psychotherapy in Ashgrove, Brisbane.

Prefer to learn by online course? You can purchase my short online course on understanding complex trauma HERE.

What is Trauma?

Trauma can be defined as is a state of high arousal in which normal coping mechanisms are overwhelmed in response to a perceived threat. Unresolved trauma leaves us with overwhelming experiences that cannot be integrated.

In Australia, there are 5 million adult survivors of childhood abuse.

Some of the additional statistics on trauma show:

1 in 3 girls will experience sexual assault by 18

1 in 4 boys will experience sexual assault by 18

1 in 4 women will experience 1 incidence of violence by an intimate partner

Trauma can be experienced in different ways including:

Attachment– lack of a consistent caregiver/parent

Developmental trauma (chronic abuse and neglect in childhood)

Single incident (eg. Natural disaster or car accident)

Single Incident (Interpersonal abuse)

Complex Trauma (Repeated Abuse)

Collective Trauma (affects an entire society)

Single Incident Trauma which is Often Known as PTSD Differs from Complex Trauma

In a single incident trauma like a car accident or natural disaster, a person experiences a beginning, middle and end. Complex trauma differs as it is repetitive, cumulative, often has no end and leave long term impacts on a person, family and community.

Complex trauma is the product of overwhelming stress which is interpersonally generated (happens in relationship) through ongoing abuse and neglect. It includes and is within the context of intimate familial relationships and also includes community violence, war or genocide.

Single incident trauma is often associated with post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD). Survivors of complex trauma may also experience PTSD and are at increased risk of PTSD. However, the impacts of complex trauma are more extensive and debilitating than PTSD on its own.

What is Complex Trauma?

Complex trauma, particularly if it occurs in childhood, has developmental deficits which do not apply to ‘single-incident’ PTSD:

‘As a group, clients with complex trauma disorders have developmental/ attachment deficits that require additional treatment focus... treatment goals are more extensive than those directed at PTSD symptoms alone’.

Clients who experience the impacts of complex trauma start at a different point. While people with single-incident PTSD need to restore their capacity to self-regulate and may have experienced a sense of safety and wellbeing prior to the traumatic event a survivor of complex trauma does not have the same starting point. They often need to learn how to self-regulate as they have not previously acquired this capacity in their early life. This has a number of implications when it comes to finding a therapist whose counselling approach is trauma-informed.

On 18th June 2018, the World Health Organisation (WHO) released the ICD-11. For the first time, a diagnosis of Complex PTSD (CPTSD) exists and will come into effect on 1st January 2022. It is important to note that there is more to trauma than PTSD and there is also more to complex trauma than Complex PTSD. The breadth of complex trauma requires a sufficiently inclusive diagnosis to fully encapsulate it with diagnosis being only one of the many lenses through which to view complex trauma.

What is Collective Trauma?

Collective Trauma refers to the psychological reactions to a traumatic event that affect an entire society.

Collective trauma does not simply reflect a historical fact or the recollection of a terrible event/s that happened to a group of people. It suggests that the tragedy is represented in the collective memory of the group. It is made up not only a reproduction of the events but also an ongoing reconstruction of the trauma in an attempt to make sense of it. Collective memory persists beyond the lives of the direct survivors of the events, and is remembered by group members that may be far removed from the traumatic event in time and space.

Complex Trauma and the Role of Attachment

Attachment patterns that form in childhood endure into early life. When effective attachment between a caregiver and an infant occurs, the infant can learn major stress modulating responses.

We know that when children receive sufficient care through adequate attachment through parents or other primary caregivers they are able to acquire generally positive expectations and interactions with others. Secure attachment and enough safety with our primary caregivers in the growing up years means that we can build on our capacities for non-verbal communication, engaging with others and responding to others.

We develop what is known as our social engagement system, and we can neurocept or pick up the cues in our environment that signal we are safe.

People who have experienced trauma typically have a compromised social engagement system and are not able to accurately neurocept or sense safety. This means that they have developed ‘faulty neuroception’ and cannot accurately tell when their environment is safe or if another person is trustworthy.

Because they are not able to sense when they are safe they are not able to inhibit their defence systems. This means that reaching out, making contact with others, autoregulation, grounding, full breathing and aligned posture becomes difficult and they may activate their defensive systems and actions including fight, flight or freeze. People who have experienced trauma often feel a sense of shame and despair as these impulses can sabotage their efforts to function day to day.

Trauma Creates Changes In our Brain

When it comes to trauma we need to understand how our experience, especially adverse experience shapes the brain. Trauma impacts not only our brain (particularly the developing brain) but also our body.

When we experience trauma we develop different behaviours and ways of being to try and cope with and regulate our trauma. You can think of this as the symptoms of trauma.

When we begin therapy to work on the symptoms of trauma it’s important to understand that the way we adapted is normal and to be expected as reactions to traumatic childhood experiences. People who have experienced trauma are not flawed, damaged or to blame for their responses to trauma.

It can be common for people who have experienced trauma to believe that they are weak or that they should be able to just ‘get over their trauma.’ They can feel a deep sense of shame whey they are not able to regulate some of the intense feelings and emotions that arise due to traumatic experience.

What we know about treating trauma is that will power or sheer determination alone will not and cannot change trauma. whilst resilience and inner strength are qualities we can develop a person who has not had these resources modelled for them growing up has not developed the ability or capacity to self-regulate. Experiences of complex trauma cannot be resolved by will power’ alone. As Dr Peter Levine states: Traumatised people cannot simply `move on’ as `the time-honoured expression `time heals all wounds’ simply does not apply to trauma.

Trauma and The Stress Response

People who have experienced complex trauma have active sympathetic nervous systems. The sympathetic nervous system is part of the automatic nervous system, which is our bodies involuntary response to dangerous or threatening situations.

When our sympathetic nervous system is engaged there is adrenalin moving through our body and we may be on alert for danger or threat. Our automatic nervous system is also what engages us in the fight, flight or freeze response.

People who have experienced trauma will have experienced one or all of the fight-flight-freeze responses at the time of trauma and when they are facing the stress of challenges afterwards.

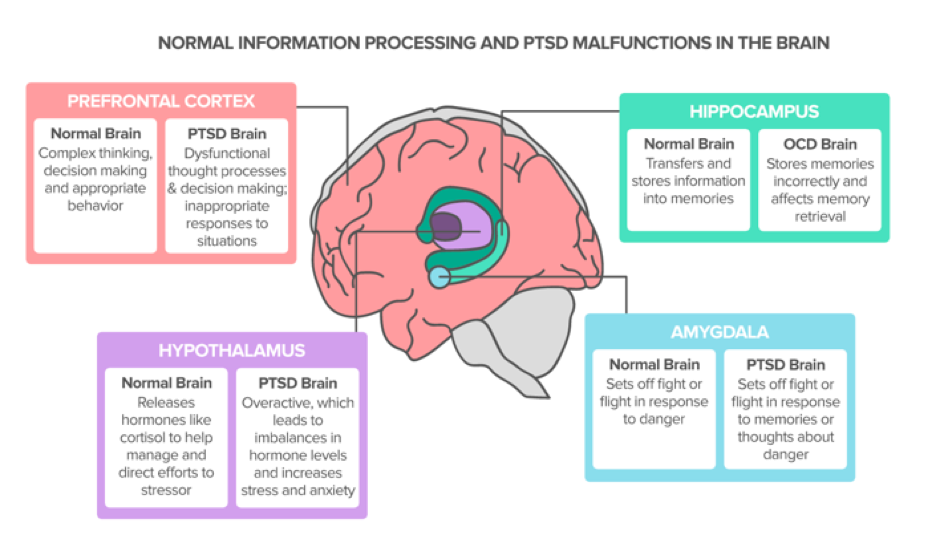

The reaction begins in your amygdala, the part of your brain responsible for perceived fear.

The amygdala responds by sending signals to the hypothalamus, which stimulates the autonomic nervous system (ANS). The ANS consists of the sympathetic and parasympathetic nervous systems. The sympathetic nervous system drives the fight-or-flight response, while the parasympathetic nervous system drives freezing. How you react depends on which system dominates the response at the time. When we have been through complex trauma it can be difficult to change our automatic behaviours.

This is because our brains act like Teflon to good experiences but velcro to bad and painful memories. We record and store bad and painful memories to ensure that we don’t forget the ways we learnt to survive so we can continue to survive in the future, even if there may now be more helpful or supportive strategies that we can use today. When comes to trying something new or changing a now unhelpful coping mechanism or behaviour to a more helpful, the brain sends us those memories of “don’t do that because last time you nearly died”. Better to mistake a stick for a snake than a snake for a stick.

This means that along with new resources, skills and supports we often need many repetitions of learning how to respond differently. We need to have repeated positive experiences as well. This isn't always as simple as it sounds. When it comes to complex trauma, one way to imagine the impact is to picture the brain that has a fire alarm going off inside it constantly. This alarm doesn’t stop ringing.

The amygdala is the ‘fire alarm system’ in our brain that’s in operation 24/7. Because we have experienced trauma, the memory is stored in our hippocampus and we draw on that old historical memory to make sense of and understand what is happening today, even if what's happening now is very different. When we get triggered by a person, event, or situation our senses are also triggered,=and our body colludes with our mind and says- That person or experience (from the past) is real, it's happening now. We enter back into what is known as “trauma time”.

Watch this video to see how stress affects the brain and see the explanation below.

Pretend this is hand is a brain. Imagine that the palm of the hand to the wrist is the part of the brain called the limbic system.

The limbic system controls the body’s automatic functions. this is where you fight, flight or freeze response is. Now the thumb will cross over the palm to represent the “mid brain.” Now the fingers cover the thumb, this represents the cortex.

When we are triggered by a traumatic event or another trigger that reminds us of a traumatic event our emotions rise up through our brain stem through our limbic system and we ‘flip our lid.’

The limbic system takes over and we can no longer access the pre-frontal cortex which is where our rational thought, problem-solving and decision making and thinking goes offline and we are driven by that fight, flight or freeze response.

Part of the work of treating complex trauma is working with a therapist to develop resources that allow you to manage your triggers not become dis-regulated or flip your lid!

Trauma Counselling

How do you work with the window of tolerance in counselling?

Many complex trauma clients have difficulty with self-regulation. This means that they find it challenging to regulate their level of arousal relating to their trauma symptoms, emotions and behaviours.

People who have experienced trauma are best able to cope with stressors and triggers when they’re operating within their window of tolerance, however, a traumatic experience can narrow your window of tolerance, leading to states of either hyper- or hypo-arousal.

Triggering leads to major dysregulation at a body level as well as psychological level. Being unable to integrate and cognitively represent bodily states can lead to distressing body complaints, concerns and symptoms as well as distressing feelings and thoughts.

When we feel dysregulated we begin to move into these different states.

Hyper-arousal is characterised by agitation and is a response to extreme anxiety.

Hypo-arousal generally manifests as a more passive flat or numb affect where the person shuts down and becomes withdrawn.

*Both of these states require different interventions and supports.

When working with trauma your therapist's role is to help you remain in the here and now and mindfully notice elements of their internal experience that support regulation.

A trauma therapist will support you by helping you to expand your regulatory capacities in the face of strong emotions or dysregulation.

If a person's physiological arousal consistency remains low or in the middle of the window of tolerance it means they will be unable to expand their capacities because they are not in contact with the disturbing residue of trauma. However, if arousal greatly exceeds at either the low or high end, new learnings and experiences cant be integrated.

The goal when working with trauma is for people to detect safety whilst experiencing some level of dysregulated affect. Therapy should remain within the ‘window of tolerance’ where a person can tolerate the sensations they are experiencing without moving into the hyper or hypo states of the window. Bit by bit you work to expand your window of tolerance as you learn the skills and resources to begin to self-regulate.

Complex Trauma and Dissociation

Many people who have experienced complex trauma also experience dissociation. Dissociation is described as the partial or complete disruption of the normal integration of a person’s psychological functioning. Dissociation is the deficiency of internal and external awareness, it’s your brain's way of supporting you ‘not to know’ what is going on.

When we are in a dissociated state, we are not paying attention and we are not present. Many clients describe this feeling as a sense of ‘being out of their body’. They may be unable to remember the conversation they had or express feeling/going “blank”. During this time we are not in touch with what is going on around us.

The reason people dissociate is to protect themselves from the challenges and fear of interpersonal contact, including contact with a therapist.

In simple terms, dissociation, i.e. disconnection from the moment, has been defined as ‘partial or complete disruption of the normal integration of a person’s psychological functioning’. Everyday forms of dissociation like daydreaming are normal however persistent activation of dissociation for defensive purposes erodes health and wellbeing. It's important be able to discern the difference between mild dissociative experiences that are normal and experiences that range from moderate to severe.

Dissociation that is problematic is frequent in complex trauma (most people with C-PTSD have experienced chronic interpersonal traumatization as children and may have severe dissociative symptoms). Structural dissociation is a dissociative division of the personality (previously known as multiple personality disorder) is an extreme defence in the face of extreme inescapable threat.

Trauma-related dissociation can be subtle and hard to recognise. A trauma-informed therapist will be paying close attention to their clients to see if they ‘zone out.’ Many clients seek therapy because they find it difficult to stay present and would like support to do so.

Complex Trauma therapy

What is the therapy for complex trauma treatment?

There is no one perfect trauma therapy treatment. The main features of complex trauma treatment reflect clinical and neurobiological insights, including the role our bodies play. They have been informed by psychodynamic work somatic (body-based) work, an understanding of trauma-based dissociation and mindfulness and Eastern principles.

Common factors research is also important as it outlines a combination of factors that contribute to the effective treatment of trauma. These include the therapeutic alliance and the relational context of therapy. Most importantly working with complex trauma there needs to be a focus on the relational, regardless of what modality a practitioner employs.

What we know about complex trauma is that disrupts different aspects of a person and their connections, including the body and brain. The focus in treating trauma is to foster those connections as well as reconnecting emotions, sensations, awareness and thoughts. Effective complex trauma involves working with a ‘bottom-up’ and ‘top-down’ approach which involves working with the body through somatic process (bottom-up) as well as working a person's emotions and thoughts (top-down).

How Long Does it take to treat complex trauma?

There is no set time frame to treat complex trauma. On average when working with complex trauma, the treatment is generally long term. For some, treatment may last years or decades, treatment on and off over their lifetime whether continuous or episodic. For others, trauma treatment may be short or brief, but it is rare that treat is both meaningful and effective is less than 10-20 sessions. Even modalities where treatment may be completed in 20-30 session may need to be repeated.

How to find a trauma counsellor to work with?

When looking to find a therapist to work with trauma it’s important to find a trauma-informed therapist who has knowledge and experience working with trauma-informed care principles and working with a 3 phase approach to treat trauma.

The Five Trauma-Informed Care Principles

Safety | Physical, emotional, environmental, cultural & systemic: A trauma counsellor will be looking at how to create an environment of safety that is welcoming, engaging and respectful. Part of ensuring safety is ensuring I support my clients to feel comfortable in the therapy space.

Trustworthiness | Clarity, consistency & interpersonal boundaries: A trauma counsellor will be looking to provide clear and consistent information around how they work. As well as communicating openly about the interpersonal boundaries of you work together.

Collaboration | maximising client choice and control: A trauma counsellor will focus on collaboration with you. They will create an opportunity for you to be a part of the planning and evaluation of your treatment. They will consult with you to ensure that your preferences are given due consideration.

Choice | Maximising collaboration and sharing power: A trauma counsellor will offer you a range of choices when working with your preferences around length of session, time of session and how you might like to be contacted. For me, it’s important that you have opportunities to make choices where possible.

Empowerment | prioritising empowerment and skills: A trauma counsellor works from a place of partnership vs working from the “expert model” of the therapist knowing it all. Trauma counselling is also about sharing power and actively recognising and supporting our client to develop this skill

These principles identify what the person who has experienced trauma did not have at the time.

The 3 Phase Treatment Approach for Complex Trauma therapy

The three-phased approach is considered the gold standard in working with complex trauma and is briefly outlined below. Please note, there is much more involved in working with trauma and this is a brief overview only.

Phase 1:Safety, stabilisation, resourcing and self-regulation

The first phase of safety and stabilisation is central and foundational to trauma counselling. It must be the focus of treatment before any work progresses to phases 2 and 3. The safety and stabilisation of phase 1 also needs to be established time and again throughout the work.

The ability to tolerate emotion is the primary task of this phase. Working with a therapist you can develop the capacity to self-regulate which includes developing strategies to become mindful and self- soothe.

Phase 1 is about learning to understand the effects of trauma. This is where you learn to recognise some of the symptoms and meanings of your body sensations, your emotions, and thoughts. With your therapist you will work to build safety and stability by:

Learning to feel safe in your own body

Learning how to calm your body and self regulate, gaining emotional stability

Establishing a safe living environment

Building stable relationships, career and supports

The goal of this stage is to create more safety and stability in your world, this supports you in being able to safely remember the trauma vs re-live it. Attempts to ‘process’ trauma without the ability to self-regulate can move a person into overwhelm and re-traumatisation.

The ability to access both internal and external resources is central to wellbeing and is radically impeded by unresolved trauma. Self-regulation depends upon the capacity to access internal resources and is also the pre-condition for trauma processing.

When we consciously and deliberately engage in practices that produce physical calmness, we signal the limbic brain that we’re safe at a physiological level.

Phase 2: Processing of traumatic memories

Processing complex trauma is a Stage 2 task and is never entered into without doing the groundwork of Phase1.

When working with processing trauma the emphasis is on the impact the trauma has had on the person vs the content or details of the trauma. The focus is to overcome the fear of traumatic memories so they can be integrated, allowing appreciation for the person you have become as a result of the trauma.

Neuroscience shows us the importance of implicit memory, and there is growing awareness that the natural emergence of traumatic memory rather than focussing on the content and details (which can be de-stabilising and re-traumatizing) is most beneficial. It is not necessary for a person’s memory to be complete to heal and recover from trauma.It’s not the details of the memory that are important; it’s the effect of what happened to the person.

The Difference Between Acknowledging and Focusing on Traumatic Material

Focusing traumatic material relates to trauma processing and requires that a person has developed enough resources before moving into this phase. Acknowledging trauma on the other hand, erodes the silence of secrecy and validates a persons distress. Judicious alluding to difficult material is thus different from talking ‘about’ it.

Acknowledging the trauma or implicit triggered memories is never unsafe, especially when we allude to ‘bad things that happened’ in a more general way without vivifying the details of them or using triggering language.

Your therapist can help you distinguish between past dangers and current triggers. Your therapist may encourage you to say out loud ‘I’m triggered’ when you are feeling distressed vs than more broad statements about feeling unsafe.

Phase 3: Integrating & Making meaning | Consolidation of treatment gains

After processing trauma from the past survivors faces can begin the task of integration and creating a new future.

This phase of treatment involves developing a new self. You can now begin to work on decreasing any feelings of shame and alienation. As you enter into more day to day life, you can overcome fears of normal life, healthy challenge and change, and intimacy. As your life becomes reconsolidated around a healthy present and a healed self, the trauma feels farther away, part of an integrated understanding of self but no longer a daily focus. You can acknowledge the ways that trauma has changed you as a person and you begin to move forward with who you are now after the trauma.

Prefer to learn by online course? You can purchase my short online course on understanding complex trauma HERE.

Natajsa Wagner is a Clinical psychotherapist providing trauma therapy and counselling services in Brisbane. As a trauma informed counsellor Natajsa's approach is deeply human and she works to recognise the wisdom inherent in all human beings. She is a trauma informed counsellor passionate about seeing people as more than their "pathology" and advocates for clinicians look beyond a person's challenges or symptoms and begin to recognise the tremendous courage and resilience of the human spirit to cope with life's experiences.